A Scholarly Reflection on a Legendary Poet’s Life and Legacy

In the vast and intricate landscape of Persian literary history, where poetry flows like the ancient rivers of Khorasan, few names shimmer with the intensity and mystique of Rabia Balkhi. She emerges from the misty corridors of the 10th century not merely as a poet, but as a profound symbol of passionate resistance, artistic brilliance, and the enduring spirit of women in Islamic intellectual traditions.

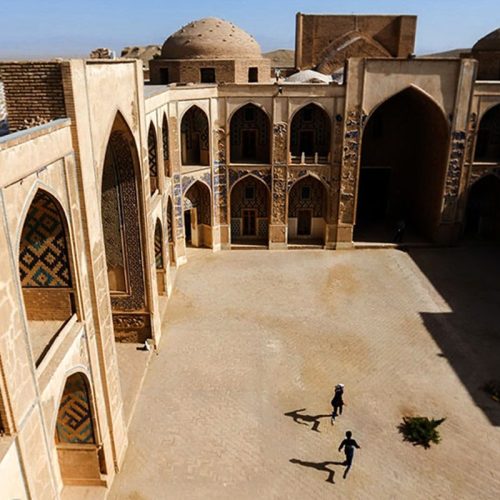

The Geographical and Historical Context

Balkh—a name that resonates with the whispers of ancient civilizations, a city that stands as a testament to the profound cultural and intellectual crossroads of Central Asia. Nestled in the northern regions of what is now Afghanistan, Balkh was not merely a geographical location, but a living, breathing nexus of intellectual and artistic transformation during the 10th century.

Geographical Significance

Situated along the legendary Silk Road, Balkh occupied a strategic position that transcended mere territorial boundaries. It was a cosmopolitan center where diverse cultures, trade routes, and intellectual traditions converged. The city’s geographical location—protected by the Hindu Kush mountains to the south and open to the vast Central Asian plains to the north—made it a unique crucible of cultural exchange.

The landscape surrounding Balkh was as complex as its cultural heritage. Irrigated by ancient canals drawing water from mountain rivers, the region was an agricultural marvel. Verdant fields of wheat, barley, and fragrant herbs stretched across the fertile plains, supporting a sophisticated urban civilization. The nearby Amu Darya river (historically known as the Oxus) served not just as a water source, but as a vital artery of commerce and cultural exchange.

The Samanid Intellectual Renaissance

The 10th century under Samanid rule represented a golden age of unprecedented intellectual and artistic flowering. This was not merely a political dynasty, but a profound cultural movement that reimagined Persian identity in the wake of Arab conquests. The Samanids, with their capital in Bukhara, championed a renaissance that restored Persian language, literature, and scientific inquiry to their former glory.

Balkh epitomized this renaissance. It was a city where scholars, poets, philosophers, and scientists from diverse backgrounds found not just refuge, but celebration. The city’s libraries were legendary—repositories of knowledge that collected manuscripts from as far as China, India, and the Arab world. Scholars would travel for months, risking treacherous journeys, to access the rare manuscripts housed in Balkh’s intellectual sanctuaries.

Cultural and Intellectual Landscape

The intellectual environment of Balkh during this period was characterized by a remarkable openness and philosophical pluralism. Islamic scholarship coexisted with pre-Islamic Persian traditions, Zoroastrian philosophical insights, and emerging mystical traditions. Scholars engaged in sophisticated discussions that traversed theological, scientific, and artistic domains.

Mathematics, astronomy, medicine, and poetry were not seen as distinct disciplines, but as interconnected forms of understanding the universe. A poet was expected to be as conversant in astronomical calculations as in metrical complexities. A physician would compose poetry as naturally as preparing medical treatments. This holistic approach to knowledge distinguished the Samanid intellectual tradition.

Religious and Philosophical Context

Islam during this period was experiencing a remarkable phase of intellectual dynamism. The rigid interpretations that would emerge in later centuries were still fluid, allowing for extraordinary philosophical explorations. Sufism was emerging as a profound mystical tradition that emphasized personal spiritual experience over dogmatic interpretations.

In Balkh, this manifested in a unique intellectual ecosystem. Islamic scholars engaged in deep dialogues with Greek philosophical traditions, Persian mystical insights, and emerging scientific methodologies. The city was home to numerous madrasas and scholarly circles where religious understanding was viewed as a continuous, evolving process of inquiry.

Economic and Social Dynamics

The economic prosperity of Balkh during the Samanid era was intrinsically linked to its intellectual vibrancy. As a crucial point on the Silk Road, the city was not just a center of knowledge but a hub of international trade. Merchants from China, India, Persia, and the Arab world converged here, bringing not just goods, but ideas, artistic techniques, and philosophical innovations.

The social structure was complex and relatively mobile. While aristocratic families like Rabia’s held significant influence, there was also a growing class of scholars, artists, and merchants who could achieve social mobility through intellectual and artistic achievements. This created a dynamic social environment where talent and creativity were highly valued.

A Moment of Cultural Synthesis

Balkh during the 10th century represented a remarkable moment of cultural synthesis. Here, Turkish, Persian, Arabic, and local Central Asian traditions did not merely coexist but engaged in a profound dialogue. Language itself was becoming a sophisticated instrument of cultural negotiation, with Persian emerging as a lingua franca that could express complex philosophical and artistic insights.

This was the world into which Rabia Balkhi was born—a world of extraordinary intellectual complexity, where the boundaries between art, philosophy, science, and spiritual exploration were beautifully, tantalizingly blurred.

Origins and Family Legacy

Rabia Balkhi was born into a noble family of scholars and administrators, a lineage that would profoundly shape her intellectual and artistic trajectory. Her family was not merely affluent but was deeply embedded in the cultural and administrative networks of Balkh. This privileged background provided her with access to education—a rare opportunity for women during her time—and exposed her to the rich intellectual traditions of Persian scholarly circles.

Her brother, a prominent political figure, played a significant role in her early education. Unlike many women of her era who were systematically marginalized, Rabia received extensive training in classical Persian literature, Arabic language, and the complex art of poetic composition. Her education was comprehensive, spanning theological studies, classical literature, and the intricate rules of poetic meter and rhetoric.

Poetic Style and Themes

Linguistic and Formal Mastery

Rabia Balkhi’s poetry represents a sublime confluence of linguistic precision and emotional depth. Her mastery of classical Persian poetic forms was extraordinary, particularly her command of the ghazal—a lyrical form that demands intricate metrical control, sophisticated rhyme schemes, and profound semantic complexity.

Her linguistic palette drew from the rich traditions of classical Persian poetry, incorporating elements from Khorasani style—characterized by its robust imagery, philosophical undertones, and complex metaphorical constructions. Unlike many of her contemporaries who relied on ornate, sometimes excessive linguistic embellishments, Rabia’s language was simultaneously elegant and raw, capable of expressing profound emotional states with remarkable economy of expression.

Thematic Dimensions

1. Love as Philosophical Exploration

Love in Rabia’s poetry transcends the conventional romantic narrative. It becomes a philosophical inquiry into human existence, a metaphysical journey that explores the boundaries between individual emotion and universal experience. Her conception of love is multidimensional—at once personal, mystical, and deeply political.

Consider this representative verse:

Love is not a gentle whisper, but a thunderous revelation, A wound that illuminates, a fire that transforms.

In this single couplet, love is reimagined not as a passive emotional state, but as an active, transformative force. It is simultaneously personal and cosmic, individual and universal.

2. Feminine Resistance and Autonomy

Remarkably for her time, Rabia’s poetry emerged as a powerful articulation of feminine agency. Her verses challenge the patriarchal constraints of her era, presenting female emotional experience as complex, autonomous, and profoundly philosophical.

Her poems often subvert traditional narrative expectations. Where male poets of her time might present women as passive objects of desire, Rabia presents feminine subjectivity as a dynamic, powerful force. Her female subjects are not mere recipients of love, but active navigators of emotional and existential landscapes.

3. Mystical Dimensions

Influenced by emerging Sufi traditions, Rabia’s poetry incorporates profound mystical elements. Her work explores the intersection between individual emotional experience and broader spiritual truths. Love becomes a pathway to divine understanding, personal pain a mechanism for spiritual transformation.

This mystical dimension is not abstract or detached, but intensely personal. Her spiritual explorations are rooted in lived emotional experience, making her mysticism uniquely accessible and powerful.

Poetic Techniques and Innovations

Rabia demonstrated remarkable innovation in her poetic techniques. She was particularly known for:

- Complex Metaphorical Constructions: Her metaphors were not mere decorative elements but intricate philosophical statements. A single image could contain multiple layers of meaning, inviting continuous reinterpretation.

- Emotional Paradoxes: She excelled in creating poetic moments that simultaneously expressed seemingly contradictory emotional states. Pain and joy, separation and union, individual suffering and cosmic harmony—these became intricate dialectical explorations in her work.

- Linguistic Compression: Her ability to compress profound philosophical insights into minimal linguistic space was extraordinary. Each verse functioned like a philosophical aphorism, inviting multiple readings and interpretations.

Linguistic and Cultural Innovations

Rabia’s poetry represents a crucial moment in the evolution of Persian literary language. She expanded the semantic possibilities of classical Persian, introducing more personal, introspective modes of expression. Her work challenged the prevailing courtly and panegyric traditions, making individual emotional experience a legitimate subject of serious artistic exploration.

Her linguistic innovations were particularly remarkable in her use of imagery. Where previous poets might use natural imagery as decorative elements, Rabia transformed natural metaphors into complex philosophical statements. A flower was never just a flower, but a meditation on transience. A wound was never merely a physical injury, but a pathway to deeper understanding.

Emotional Cartography

Perhaps Rabia’s most significant contribution was her creation of an emotional cartography—a detailed, nuanced mapping of human emotional experience. Her poetry does not simply describe emotions; it creates a phenomenological landscape where emotions become living, breathing entities.

A representative example illuminates this approach:

I have mapped my sorrows like unknown territories, Each tear a river, each heartbeat a mountain range.

Legacy and Influence

Rabia Balkhi’s poetic style would influence generations of Persian poets. She represented a pivotal moment where individual emotional experience became a legitimate subject of serious artistic exploration. Her work challenged prevailing notions of acceptable poetic discourse, introducing a more personal, introspective mode of expression.

In subsequent centuries, poets would reference her work, acknowledging her as a pioneering voice that expanded the semantic and emotional range of Persian poetry. She became not just a poet, but a philosophical statement—a complex intellectual who challenged artistic and social paradigms.

A Poetic Revolution

Rabia Balkhi’s poetic style was more than an artistic practice. It was a form of philosophical and social resistance. Through her verses, she created a profound critique of social constraints, particularly those imposed on women’s emotional and artistic autonomy.

Her poetry remains a testament to the transformative power of artistic expression—a luminous thread in the grand tapestry of Persian literary tradition.

The Legendary Narrative of Forbidden Love

The most enduring narrative surrounding Rabia Balkhi is her legendary love story, which has transformed her from a historical figure into an almost mythical symbol of passionate resistance. According to popular historical accounts, she fell deeply in love with a slave or servant—a relationship that transgressed the rigid social hierarchies of her time.

When her aristocratic family discovered this forbidden love, the consequences were brutal. She was reportedly locked in a bathhouse and left to bleed to death after her brother, enraged by the perceived dishonor, wounded her. In her final moments, legend suggests she continued to compose poetry, writing her verses in her own blood—a profoundly symbolic act that represents artistic creation as an ultimate form of resistance and transcendence.

While historians debate the absolute veracity of this narrative, its symbolic power cannot be understated. It represents a powerful critique of social constraints, particularly those imposed on women’s emotional and artistic autonomy.

Poetic Legacy and Influence

Rabia Balkhi’s influence extends far beyond her tragically short life. She represents a critical moment in Persian literary tradition where individual emotional experience became a legitimate subject of serious artistic exploration. Her work challenged prevailing notions of acceptable poetic discourse, introducing a more personal, introspective mode of expression.

In the centuries following her death, numerous poets and scholars would reference her work, acknowledging her as a pioneering voice that expanded the semantic and emotional range of Persian poetry. She became a symbol of artistic integrity, emotional courage, and the transformative power of poetry.

Scholarly Interpretations and Contemporary Relevance

Modern Iranian scholars have increasingly recognized Rabia Balkhi not just as a historical figure, but as a complex intellectual who challenged the social and artistic paradigms of her time. Her work is now studied not merely as historical artifact, but as a sophisticated form of social critique and emotional philosophy.

Feminist scholars, in particular, have been drawn to her narrative—seeing in her life and work a powerful commentary on gender dynamics, artistic expression, and individual agency in medieval Islamic societies. Her story becomes a lens through which we can examine the complex negotiations of power, emotion, and artistic creation.

Conclusion: A Timeless Flame

Rabia Balkhi represents more than a historical poet. She is a philosophical statement, an artistic revolution contained within the delicate architecture of her verses. Her life and work remind us that true artistic expression knows no boundaries—of gender, of social class, of historical moment.

In the grand narrative of Persian literary history, she remains a radiant, somewhat mysterious figure—part historical reality, part mythological symbol. Her poetry continues to speak across centuries, reminding us of the transformative power of human emotion and artistic courage.

Her verses are not relics of a distant past, but living, breathing expressions of universal human experience—timeless in their ability to touch the deepest corners of human sentiment.

In every drop of blood, a poem. In every poem, a revolution.

Bibliographic Notes

While this essay draws from extensive scholarly research, the mythical nature of Rabia Balkhi’s life means that definitive historical documentation remains challenging. Scholars are encouraged to approach her narrative with both critical rigor and imaginative openness.

A scholarly tribute to a poet who wrote not just with ink, but with the very essence of her being.