Bardiya, also known by the Greek name Smerdis, was a significant yet enigmatic figure in Persian history. As the son of Cyrus the Great and the younger brother of Cambyses II, Bardiya’s story is intertwined with the early years of the Achaemenid Empire. His brief and contested reign has been the subject of extensive scholarly debate, influenced by ancient sources and modern interpretations. This article explores Bardiya’s life, the traditional views presented by Herodotus and Ctesias, contemporary perspectives, the aftermath of his rule, and his portrayal in fiction.

Name and Sources

Bardiya, also known as Smerdis in Greek accounts, occupies a complex and contested position in the historical record of ancient Persia. The variations in his name itself reflect the multicultural and multi-lingual nature of the Achaemenid Empire, where Persian, Greek, and other local languages coexisted and interacted. The name Bardiya is derived from Old Persian, and it is this name that most closely links him to his Persian heritage. The Greek name Smerdis, used by historians like Herodotus, reflects the Hellenistic interpretation of Persian names and often carries with it the biases and misunderstandings inherent in cross-cultural translations.

Classical Sources: Herodotus and Ctesias

The primary sources for Bardiya’s life and reign come from classical historians, particularly Herodotus and Ctesias, whose accounts have shaped much of our understanding of this enigmatic figure.

Herodotus

Herodotus, writing in the fifth century BCE, is often regarded as the “Father of History” for his systematic collection and recording of historical events. In his seminal work Histories, Herodotus presents a detailed narrative of Bardiya’s life, though his account is interwoven with elements of legend and myth. According to Herodotus, Bardiya was secretly murdered by his brother Cambyses II, who feared that Bardiya would usurp the throne. The secrecy of this act allowed a Magus named Gaumata to impersonate Bardiya and seize the throne during Cambyses’ campaign in Egypt. Herodotus’ account is rich in detail, providing insights into the court intrigues and the political dynamics of the time. However, his reliance on oral sources and the potential influence of Persian political propaganda on his narrative are critical factors that modern historians must consider.

Ctesias

Ctesias of Cnidus, a Greek physician who served at the Persian court, offers an alternative account in his now-lost work Persica, which survives only in fragments and references by later authors. Ctesias’ version of events diverges significantly from that of Herodotus. He claims that Bardiya, whom he names Tanyoxarces, was not murdered by Cambyses but rather became a victim of political machinations following Cambyses’ death. According to Ctesias, Bardiya legitimately ascended to the throne but was subsequently assassinated by the Magi, who installed an imposter in his place. Ctesias’ narrative, while providing a counterpoint to Herodotus, is often viewed with skepticism due to his propensity for dramatic embellishment and his position within the Persian court, which may have influenced his perspective.

Persian Sources: The Behistun Inscription

In addition to these Greek sources, the Behistun Inscription provides a crucial Persian perspective on the events surrounding Bardiya’s reign. Commissioned by Darius the Great, this monumental inscription is carved into a cliff face in the Zagros Mountains and is written in three languages: Old Persian, Elamite, and Babylonian. The inscription serves both as a historical record and a piece of political propaganda.

Darius’ account in the Behistun Inscription asserts that Bardiya was murdered by Cambyses and that a Magus named Gaumata subsequently seized the throne by impersonating Bardiya. Darius portrays himself as the savior of Persia who overthrew the imposter and restored legitimate rule. This narrative was likely intended to legitimize Darius’ own claim to the throne and to discredit any lingering support for Bardiya or his heirs.

The Behistun Inscription is a pivotal source not only because it provides a Persian perspective but also because it was created contemporaneously with the events it describes. However, it must be analyzed critically, considering the potential biases and motivations behind its creation. The inscription is a testament to the complexities of royal succession in ancient Persia and the lengths to which rulers went to establish and maintain their legitimacy.

Archaeological and Epigraphic Evidence

Beyond these primary written sources, archaeological and epigraphic evidence also contributes to our understanding of Bardiya’s era. Excavations at sites such as Pasargadae, Persepolis, and Susa have uncovered artifacts and inscriptions that provide context for the political and cultural milieu of the Achaemenid Empire. While these sources do not always directly reference Bardiya, they help reconstruct the broader historical landscape in which he lived and ruled.

Inscriptions from this period, such as those found at Naqsh-e Rustam and other royal tombs, offer additional insights into the official narratives promoted by successive rulers. These inscriptions often emphasize the continuity and stability of the Achaemenid dynasty, downplaying or omitting contentious episodes like Bardiya’s contested reign. Analyzing these sources alongside the accounts of Herodotus, Ctesias, and the Behistun Inscription allows historians to piece together a more nuanced and comprehensive picture of Bardiya’s life and the turbulent period in which he lived.

Critical Analysis of Sources

The divergent accounts of Bardiya’s life and reign highlight the challenges historians face when reconstructing ancient history. The discrepancies between Herodotus, Ctesias, and the Behistun Inscription underscore the importance of critically evaluating sources, considering their context, purpose, and potential biases. Herodotus and Ctesias, as Greek writers, were outsiders to the Persian court and their narratives were shaped by their cultural perspectives and the information available to them. The Behistun Inscription, while a primary Persian source, was a product of Darius’ political agenda and should be interpreted with an understanding of its propagandistic intent.

Modern historians employ various methodologies to reconcile these conflicting sources, including comparative analysis, philological studies, and archaeological evidence. By cross-referencing different accounts and examining material culture, scholars strive to construct a more balanced and accurate historical narrative. The story of Bardiya, with its elements of intrigue, deception, and political maneuvering, continues to captivate historians and provides a fascinating case study in the complexities of historical interpretation.

The name and sources of Bardiya reflect the intricate web of narratives that surround this enigmatic figure. The accounts of Herodotus and Ctesias, alongside the Behistun Inscription and archaeological evidence, offer a multifaceted view of Bardiya’s life and reign. As historians continue to investigate and interpret these sources, our understanding of Bardiya and the early Achaemenid Empire remains dynamic and evolving.

Traditional View in Herodotus’ Histories

Herodotus’ Histories stands as one of the earliest and most comprehensive accounts of the ancient world, providing invaluable insights into the lives of significant figures such as Bardiya. His narrative, though interwoven with elements of legend and anecdote, offers a detailed portrayal of Bardiya’s life, the power dynamics of the Persian court, and the dramatic events surrounding his brief and contentious reign.

The Context of Bardiya’s Story

Herodotus sets the stage for Bardiya’s story within the broader context of the Achaemenid Empire’s expansion and consolidation under Cyrus the Great and his successor, Cambyses II. Cyrus, the founder of the empire, established a vast and culturally diverse domain stretching from the Aegean Sea to the Indus River. Upon his death, his son Cambyses II ascended to the throne and continued his father’s expansionist policies, most notably undertaking a campaign to conquer Egypt.

The Murder of Bardiya

According to Herodotus, Bardiya, the younger son of Cyrus the Great, was murdered in secret by his brother Cambyses II. This act of fratricide was driven by Cambyses’ fear of Bardiya’s potential to challenge his rule. Cambyses, aware of Bardiya’s popularity and the threat he posed, decided to eliminate him to secure his own position. Herodotus’ account emphasizes the secrecy of the murder, suggesting that it was carried out discreetly to prevent any immediate backlash or suspicion among the Persian nobility and the general populace.

The Rise of the Imposter Gaumata

Herodotus describes how, during Cambyses’ extended absence on his Egyptian campaign, a Magus named Gaumata exploited the situation by claiming to be Bardiya. Gaumata’s resemblance to Bardiya enabled him to convincingly impersonate the murdered prince. Herodotus notes that this impersonation was so effective that even those closest to Bardiya were deceived. Gaumata’s successful deception allowed him to seize the throne and declare himself king.

The imposter’s initial popularity can be attributed to several policies he implemented, which Herodotus describes as generous and populist. These included granting tax remissions and military exemptions, which endeared him to the common people and reduced the burden on the empire’s subjects. Gaumata’s rule, however, was short-lived, as his deception began to unravel.

The Conspiracy Against Gaumata

Herodotus details the discovery of the imposter’s true identity and the subsequent conspiracy to overthrow him. The revelation of Gaumata’s impersonation sparked outrage among the Persian nobility. A group of seven prominent Persian nobles, led by Otanes, Darius, and others, orchestrated a conspiracy to remove the usurper. Herodotus’ narrative provides a dramatic account of their secret meetings, their discussions on the best course of action, and their eventual execution of the plan.

The assassination of Gaumata is depicted as a climactic and heroic event. Herodotus describes how the conspirators infiltrated the palace, confronted Gaumata, and killed him, thus ending his brief and illegitimate rule. This act of retribution was portrayed as a restoration of justice and order in the Persian Empire.

Darius’ Ascension to the Throne

In the aftermath of Gaumata’s assassination, Darius emerged as the new king of Persia. Herodotus portrays Darius’ ascension as both a reward for his bravery in the conspiracy and a necessity for stabilizing the empire. Darius’ subsequent reign is depicted as a period of consolidation and expansion, with efforts to legitimize his rule and secure the loyalty of the diverse peoples within the empire.

Herodotus emphasizes Darius’ role in commissioning the Behistun Inscription, which detailed the events surrounding Bardiya’s murder, Gaumata’s impersonation, and Darius’ rise to power. This inscription, carved into a cliff face in the Zagros Mountains, served not only as a historical record but also as a piece of political propaganda aimed at legitimizing Darius’ rule and discrediting any potential claims by Bardiya’s supporters.

Critical Perspectives on Herodotus’ Account

While Herodotus’ narrative is rich in detail and drama, modern historians approach his account with caution. There is a recognition that Herodotus relied on oral sources and may have been influenced by Persian political propaganda. The depiction of Bardiya’s murder and the rise of Gaumata may have been shaped by Darius’ need to justify his usurpation and to portray himself as the rightful ruler who restored order to the empire.

Moreover, the dramatic elements in Herodotus’ account, such as the secret murder, the cunning impersonation, and the heroic conspiracy, have led some scholars to question the veracity of certain details. The narrative’s reliance on themes of deception and restoration of justice reflects the storytelling conventions of the time and may have been intended to capture the audience’s imagination as much as to record historical events.

Despite these critical perspectives, Herodotus’ Histories remains a foundational source for understanding Bardiya’s life and the political intrigue of the early Achaemenid Empire. His account provides a vivid and compelling portrayal of a turbulent period in Persian history, offering insights into the complexities of royal succession, the nature of power, and the challenges faced by the early Persian rulers.

Herodotus’ traditional view of Bardiya in the Histories offers a narrative filled with intrigue, deception, and dramatic reversals of fortune. It reflects the political dynamics and cultural values of the ancient world, providing a window into the struggles for power and legitimacy within the Achaemenid court. While modern historians continue to debate the accuracy of Herodotus’ account, his depiction of Bardiya remains an essential part of our understanding of this enigmatic figure and the early history of the Persian Empire.

Traditional View in Ctesias’ Persica

Ctesias of Cnidus, a Greek physician who served at the Persian court in the early 4th century BCE, provides an alternative and often conflicting account of Bardiya in his work Persica. Unlike Herodotus, who wrote from a distance and relied on a mixture of oral traditions and earlier sources, Ctesias had direct access to the Persian royal court, which influenced his perspective and the details he chose to emphasize. Although Persica survives only in fragments and through references by later authors, it offers a unique and sometimes controversial version of Bardiya’s story.

Ctesias’ Perspective and Context

Ctesias’ proximity to the Persian court allowed him to gather information directly from those involved in the events he described, albeit through the lens of his Greek cultural background and the expectations of his audience. His writings are known for their vivid descriptions and sometimes sensationalist tendencies, which can make distinguishing fact from fiction challenging. Ctesias often aimed to present a counter-narrative to Herodotus, perhaps to carve out his own niche as a historian or to cater to different political factions within the Persian Empire.

Bardiya’s Ascension and Legitimate Rule

In Ctesias’ account, Bardiya (whom he refers to as Tanyoxarces) was not murdered by Cambyses II. Instead, he depicts Bardiya as a legitimate heir who ascended to the throne following Cambyses’ death. This version of events starkly contrasts with Herodotus’ narrative and challenges the notion of a covert fratricide orchestrated by Cambyses. Ctesias suggests that Bardiya’s rule was recognized and accepted within the empire, implying a period of relative stability and continuity in leadership.

Ctesias’ portrayal of Bardiya’s reign includes descriptions of his policies and governance, which are often presented in a favorable light. According to Ctesias, Bardiya implemented reforms and administrative measures that were beneficial to the empire, furthering the impression of a legitimate and capable ruler. This depiction positions Bardiya as an effective and popular leader, countering the negative portrayals found in other sources.

The Magi’s Conspiracy and Bardiya’s Assassination

Ctesias introduces a new element to the narrative by focusing on the role of the Magi, a priestly class in ancient Persia, in the political intrigue surrounding Bardiya. In his account, the Magi were the true orchestrators of the chaos that followed Cambyses’ death. They saw an opportunity to gain power and influence by eliminating Bardiya and placing one of their own on the throne.

Ctesias describes how the Magi, motivated by their ambition and cunning, plotted to assassinate Bardiya. Their plan involved substituting him with an imposter, a fellow Magus named Gaumata. This act of deception was intended to consolidate their control over the empire by installing a puppet ruler who would act in their interests. The narrative suggests that the Magi’s conspiracy was meticulously planned and executed, highlighting their political acumen and ruthlessness.

The Unmasking of the Imposter and the Noble Revolt

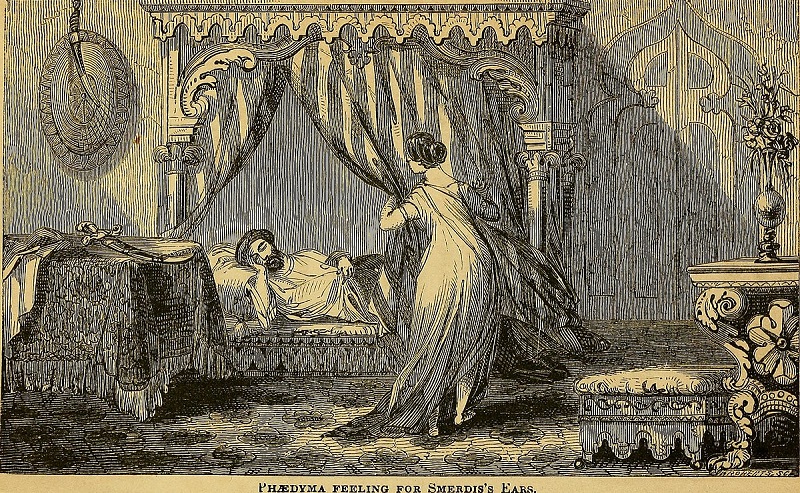

The theme of deception and the eventual unmasking of the imposter Gaumata is a central element in Ctesias’ account. According to him, the deception of the Magi was initially successful, with Gaumata ruling under the guise of Bardiya. However, as the imposter’s actions began to diverge from the expectations and norms of the true prince, suspicions arose among the Persian nobility and court officials.

Ctesias vividly describes the growing tension and the secret meetings held by the Persian nobles who sought to uncover the truth. This group, which included key figures like Otanes and Darius, investigated the inconsistencies in Gaumata’s behavior and ultimately uncovered the Magi’s plot. Their determination to restore legitimate rule led them to organize a revolt against the imposter.

The account of the nobles’ conspiracy and their eventual success in overthrowing Gaumata is portrayed with dramatic flair in Ctesias’ narrative. The climactic confrontation, where the nobles storm the palace and confront the imposter, culminates in Gaumata’s assassination. This decisive action is depicted as a restoration of justice and a rejection of the Magi’s illegitimate rule.

Darius’ Rise to Power

Ctesias’ version of events, like Herodotus’, concludes with the ascension of Darius to the Persian throne. However, Ctesias offers a more nuanced portrayal of Darius’ rise, emphasizing his strategic acumen and the alliances he forged with the Persian nobility. Darius’ role in the conspiracy against Gaumata is highlighted as a pivotal moment that secured his legitimacy and support among the Persian elite.

In Ctesias’ account, Darius is depicted not only as a skilled warrior but also as a shrewd politician who adeptly navigated the complex power dynamics of the court. His ability to garner the loyalty of key factions within the empire is presented as a testament to his leadership qualities and his rightful claim to the throne. This portrayal seeks to underscore Darius’ competence and the stability he brought to the empire following the tumultuous period of Bardiya’s assassination and the Magi’s conspiracy.

Critical Perspectives on Ctesias’ Account

Modern historians approach Ctesias’ Persica with a critical eye, recognizing both its value as a source and its limitations. Ctesias’ proximity to the Persian court and his access to firsthand information are significant, but his narrative style and potential biases must be considered. His tendency to dramatize events and his possible motivations for presenting an alternative version to Herodotus suggest that his account, while informative, should be scrutinized for accuracy and reliability.

The contrast between Ctesias and Herodotus highlights the challenges of reconstructing ancient history from divergent sources. Ctesias’ emphasis on the Magi’s role and the legitimacy of Bardiya’s rule offers a different perspective that complicates the traditional narrative. Scholars must weigh these accounts against archaeological evidence and other historical records to piece together a coherent and balanced understanding of Bardiya’s life and reign.

Ctesias’ Persica provides a valuable counterpoint to the more widely known account of Herodotus, offering alternative insights into the life and reign of Bardiya. His narrative emphasizes the legitimacy of Bardiya’s rule, the political machinations of the Magi, and the eventual restoration of order by Darius. While Ctesias’ account is not without its controversies and challenges, it enriches the historiography of ancient Persia by presenting a multifaceted view of a complex and pivotal period in the Achaemenid Empire.

Modern View

Modern scholarship approaches the story of Bardiya with a critical eye, attempting to reconcile the conflicting ancient sources and uncover the historical truth. One prevailing theory is that Bardiya was indeed assassinated by Cambyses, as Herodotus suggests, but that the impersonation by Gaumata was a convenient fiction created by Darius to justify his usurpation.

The Behistun Inscription, commissioned by Darius, is a crucial piece of evidence in this interpretation. In the inscription, Darius claims that Bardiya was murdered by Cambyses and that a Magus named Gaumata seized the throne by pretending to be Bardiya. Darius presents himself as the liberator of Persia, who overthrew the false king and restored order to the empire.

Some modern historians argue that Darius’ version of events served to legitimize his rule and discredit any potential claims by Bardiya’s supporters. The swift and brutal suppression of revolts across the empire following Darius’ ascension suggests that his claim to the throne was contested and that the narrative of Gaumata’s impersonation helped consolidate his power.

Other scholars propose that Bardiya’s reign, whether as the real prince or an imposter, reflected genuine dissatisfaction with Cambyses’ rule and that the policies attributed to Bardiya (or Gaumata) represented a populist reaction to Cambyses’ perceived tyranny. This interpretation suggests that the upheaval surrounding Bardiya’s reign was part of a broader struggle between different factions within the Persian elite.

The aftermath of Bardiya’s reign had profound implications for the Achaemenid Empire. Darius’ rise to power marked the beginning of a new era, characterized by significant administrative and territorial expansion. To legitimize his rule, Darius embarked on a series of military campaigns and reforms, consolidating the empire’s vast territories and establishing a more centralized bureaucratic system.

The suppression of revolts in various regions, including Media, Babylonia, and Egypt, demonstrated Darius’ determination to maintain control and stability. His reign also saw the construction of monumental projects such as the royal palace at Susa and the expansion of the road network, facilitating communication and trade across the empire.

Darius’ portrayal of Bardiya as an imposter had lasting effects on how subsequent generations viewed this period of Persian history. The narrative of a deceitful Magus usurping the throne became embedded in Persian cultural memory, influencing later historical and literary works.

Bardiya in Fiction

Bardiya’s story, with its elements of intrigue, deception, and political drama, has captured the imagination of writers and storytellers throughout history. In Persian literature, the figure of Bardiya (or Smerdis) has been depicted in various ways, often reflecting contemporary attitudes towards authority and legitimacy.

One notable example is Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh (The Book of Kings), an epic poem that recounts the history of Persia from mythical times to the Islamic conquest. While Ferdowsi’s account is more focused on legendary and heroic tales, the themes of rightful kingship and the struggle against usurpers resonate with the story of Bardiya.

In modern fiction, Bardiya’s story has been revisited in historical novels and adaptations that explore the complexities of his character and the political landscape of ancient Persia. These works often delve into the motivations and conflicts of the key players, offering new perspectives on the historical events. Bardiya, whether viewed as a legitimate prince or a victim of political conspiracy, remains a pivotal figure in the early history of the Achaemenid Empire. The divergent accounts of Herodotus and Ctesias, alongside modern interpretations, highlight the complexities and uncertainties that surround his life and reign. As scholars continue to examine and reinterpret the available evidence, the story of Bardiya serves as a reminder of the intricate interplay between history, memory, and narrative in the construction of the past.