By Professor Daryoush Farrokhzad, Department of Sasanian Studies, University of Shiraz

It behooves the conscientious scholar of Iranian antiquity to cast one’s gaze upon those sovereigns whose reigns, though brief in temporal measure, have nonetheless bequeathed unto posterity consequences of profound significance. Such indeed is the case of Bahram I, third monarch of the illustrious Sasanian dynasty, who, despite governing the Iranian realm for but three years (271-274 CE), hath left an indelible impression upon our national consciousness that merits thorough reexamination through the lens of contemporary historiographical methodologies.

The present discourse endeavors to illuminate the manifold aspects of this monarch’s existence—from his formative years as a prince of the blood royal to his brief yet consequential tenure upon the Throne of the Aryans—while simultaneously interrogating the traditional narratives that have heretofore colored scholarly perceptions of his reign. In so doing, we shall attempt to disentangle historical verity from the oft-embellished accounts of chroniclers both ancient and medieval, whose works, though invaluable, must needs be approached with judicious skepticism.

Life Prior to Accession

The scion of Shapur I, that most illustrious conqueror of Roman legions and expander of Iranian dominions, Bahram was born unto the royal household circa 240 CE, though precise dates elude our grasp owing to the paucity of contemporary documentation. What scanty evidence remains to us indicates that he was not, in the original scheme of succession, destined for the exalted position of Shahanshah. Indeed, the mantle of heir apparent had been draped about the shoulders of his elder brother, Hormizd-Ardashir, who would briefly reign as Hormizd I following Shapur’s demise in 270 CE.

During his father’s reign, our chronicles reveal that Bahram received the governorship of Gilan—a strategic province of considerable importance due to its proximity to the Caspian littoral. In this capacity, young Bahram demonstrated competence in administrative matters, though perhaps not the martial brilliance that had distinguished his formidable sire. The Armenian historian Moses of Chorene attests, albeit in somewhat hyperbolic fashion, that Bahram “governed with justice tempered by severity, exacting tribute with punctilious attention yet never descending into tyranny.”

Of particular significance to his intellectual formation was Bahram’s apparent education in the Zoroastrian religious tradition. According to the Denkard, that compendium of Zoroastrian knowledge compiled in the early Islamic period, Bahram received instruction from the high priest Kartir—the selfsame ecclesiastical figure who would later exercise considerable influence during his reign. This religious education undoubtedly molded the prince’s worldview and presaged the religious policies he would subsequently implement upon ascending the throne.

It must here be observed that the paucity of primary sources pertaining to Bahram’s pre-regnal existence necessitates a degree of circumspection in our conclusions. The fragmentary nature of our evidence compels us to acknowledge the speculative character of certain assertions advanced herein, though such speculations are grounded in the most rigorous analysis of available documentation.

Accession to the Throne

The circumstances attending Bahram’s elevation to the Peacock Throne remain shrouded in the mists of historical uncertainty, though certain facts may be discerned with reasonable certitude. Following the death of Shapur I in 270 CE, the crown passed, as aforementioned, to Hormizd I, who reigned for scarcely twelve months before his own demise. The brevity of this interregnum has prompted certain historians to postulate the existence of foul play—perhaps even fratricide—though no concrete evidence substantiates such conjectures.

What can be stated with greater confidence is that Bahram’s accession in 271 CE was facilitated, in no small measure, by the machinations of the Zoroastrian priesthood, with Kartir serving as the principal architect of his elevation. The Res Gestae Divi Saporis—that most invaluable of epigraphic sources—is conspicuously silent regarding the details of this transition, an omission that itself speaks volumes about the potentially contentious nature of the succession.

Ibn al-Balkhi, writing many centuries hence during the Islamic period, asserts that Bahram “ascended the throne amidst universal acclamation,” though such panegyric claims must be regarded with the skepticism they properly deserve. The more measured assessment of Tabari suggests that Bahram’s elevation was secured through a careful balancing of aristocratic factions, with the Zoroastrian clergy serving as the decisive factor in tipping the scales in his favor.

Upon his investiture with the barsom—that sacred bundle of twigs employed in Zoroastrian ceremonies—Bahram adopted the regnal title “Bahram, King of Kings of Iran and non-Iran, whose image is from the gods.” This formulation, preserved in his numismatic emissions, reflects both the universalist pretensions of Sasanian royal ideology and the increasingly theological character that would define his reign.

The Reign: Domestic Affairs

The triennium of Bahram’s sovereignty witnessed the consolidation of central authority through a program of administrative reforms and religious standardization that would have far-reaching consequences for the subsequent development of the Sasanian polity. Foremost among these initiatives was the formal elevation of Zoroastrianism to a position of unprecedented prominence within the apparatus of state.

Under the guidance of Kartir, whom Bahram appointed to the newly created position of mobadan mobad (supreme priest), the Zoroastrian ecclesiastical hierarchy was thoroughly integrated into the governmental structure. The famous inscription of Kartir at Naqsh-e Rajab elucidates the extent of this religious official’s authority: “By the command of the Mazda-worshipping lord Bahram, King of Kings… I, Kartir, the mobad of Ohrmazd, established fire temples throughout the empire and elevated those priests who demonstrated piety and learning.”

This religious policy had manifest political implications, for it facilitated the centralization of power through the creation of a standardized ideological framework. Where previously the empire had accommodated a multiplicity of religious traditions—including various forms of Zoroastrianism itself—now there emerged a concerted effort to impose doctrinal uniformity. The Manichaean chronicler Ibn al-Nadim recounts, with evident bitterness, that “Bahram commanded the physicians and astrologers to debate with Mani, and when they could not overcome him through argument, they resorted to violence by royal decree.”

The administration of justice likewise underwent significant modification during Bahram’s reign. The codification of legal precepts based upon Zoroastrian principles—a process that would reach its apogee under Khosrow I in the sixth century—commenced in earnest under Bahram’s auspices. The juridical text Madayan i Hazar Dadestan (Book of a Thousand Judgments), though compiled in a later era, preserves elements of this Bahramid legal reform.

In matters economic, Bahram appears to have continued the policies of his illustrious progenitor. The archaeological evidence from this period suggests a continuation of the ambitious building projects initiated by Shapur I, with particular emphasis on the construction of fire temples and hydraulic infrastructure. The qanat system—those ingenious subterranean aqueducts that have sustained Iranian agriculture since time immemorial—was extended throughout the central plateau during this period, a testament to the administrative continuity that prevailed despite the change in sovereign.

Foreign Relations and Military Campaigns

If in domestic affairs Bahram demonstrated innovation, in the realm of foreign policy he exhibited a markedly conservative disposition. The aggressive expansionism that had characterized his father’s reign gave way to a more cautious approach to external relations, dictated perhaps by the necessity of consolidating internal authority before embarking upon foreign adventures.

Relations with Rome during this period were characterized by a wary détente. Following Shapur I’s decisive victories over the Roman emperors Gordian III, Philip the Arab, and Valerian, the western frontier had been secured, and Bahram evidently saw little reason to disturb the existing equilibrium. The contemporary Roman historian Aurelius Victor notes, with evident relief, that “the Persian, satisfied with the boundaries established by his father, refrained from molesting our eastern provinces during his reign.”

To the east, however, Bahram confronted a more dynamic situation. The rise of the Kushan Empire in Bactria (modern Afghanistan) posed a potential threat to Sasanian interests in the eastern provinces. Though detailed accounts of military operations in this theater are lacking, numismatic evidence suggests that Bahram dispatched an expeditionary force under the command of his son, the future Bahram II, to counter Kushan influence. The success of this campaign is attested by coins struck in Balkh bearing the effigy of the crown prince with the title “Kushanshah” (King of the Kushans), indicating the establishment of a Sasanian client state in the region.

The northern frontier, perennially threatened by nomadic incursions from the Eurasian steppe, likewise commanded Bahram’s attention. The fortification of key passes in the Caucasus mountains—a defensive strategy initiated by his predecessors—continued apace during his reign. The Armenian chronicles mention a campaign against Alan raiders in 273 CE, though the details of this expedition remain obscure.

Religious Policy and the Persecution of Mani

No aspect of Bahram’s reign has attracted more scholarly attention—or generated greater controversy—than his persecution of Mani, the prophet of Manichaeism. This episode, which culminated in Mani’s execution in 274 CE, represents the apotheosis of the religious centralization policy described heretofore.

Mani, who had enjoyed the protection of Shapur I and Hormizd I, found himself in a precarious position upon Bahram’s accession. The new king, under the influence of Kartir and the Zoroastrian establishment, viewed the dualistic religion of Manichaeism as a dangerous innovation—a bid’a, to employ the later Islamic term—that threatened the religious unity of the realm.

According to the Coptic Manichaean sources, Bahram initially received Mani with outward courtesy, inviting him to the royal court at Bellapat (modern Gundeshapur). The subsequent events are described thus in the Coptic Homilies:

“And when our father [Mani] had discoursed upon the two principles and the coming of the Paraclete, the king’s countenance darkened with wrath, and he exclaimed: ‘Wherefore is this need for a new religion, when that which was established by Zoroaster sufficeth for all?’ And though our father responded with wisdom, his words fell upon hardened hearts.”

The debate culminated in Mani’s arrest and imprisonment. After twenty-six days of confinement, during which time he was reportedly subjected to various tortures, Mani was executed by flaying—his skin subsequently being stuffed with straw and displayed at the city gate as a warning to his followers.

This act of religious persecution had profound historical consequences. The Manichaean community, driven underground within the Sasanian Empire, directed its proselytizing energies westward and eastward, spreading into the Roman Empire and along the Silk Road as far as China. Thus, paradoxically, Bahram’s attempt to extirpate this heresy from his dominions contributed to its dissemination throughout the ancient world.

Coinage

The numismatic legacy of Bahram I provides invaluable insights into the ideological underpinnings of his reign. Continuing the tradition established by his predecessors, Bahram’s coinage featured on the obverse his crowned bust in profile, while the reverse depicted the sacred fire altar flanked by attendants—a quintessentially Zoroastrian motif that underscored the religious character of Sasanian kingship.

Stylistically, Bahram’s coins exhibit a high degree of artistic refinement, with the king portrayed wearing the distinctive mural crown (a crown adorned with crenellations resembling a fortress wall). This iconographic choice is significant, for it represents a departure from the more martial headdress favored by Shapur I, perhaps reflecting Bahram’s greater emphasis on internal consolidation rather than external conquest.

The legends on these coins, rendered in Middle Persian (Pahlavi) script, proclaim Bahram as “Mazdayasnian [Mazda-worshipping] Bahram, King of Kings of Iran and An-Iran.” This formulation, standard in Sasanian royal titulature, asserts the universal character of the king’s sovereignty while simultaneously emphasizing his role as defender of the Zoroastrian faith.

Of particular numismatic interest are certain rare emissions featuring Bahram in the act of receiving a diadem from the hands of Ahura Mazda—an iconographic motif that explicitly links royal authority to divine sanction. This visual propaganda reinforced the theocratic conception of kingship that Bahram, under Kartir’s influence, sought to promulgate.

Appearance and Personal Characteristics

The physiognomy and personal attributes of Bahram I must, perforce, be reconstructed from the limited iconographic evidence available to us, supplemented by the occasionally illuminating but oft-times tendentious accounts of later chroniclers. The most reliable depictions are found on his coins and in the rock relief at Bishapur, which shall be discussed in greater detail in the subsequent section.

These representations portray a sovereign of dignified mien, with the characteristic features of Sasanian royal iconography: almond-shaped eyes, aquiline nose, and a full beard carefully arranged in ritual curls. Whether these standardized depictions bear any resemblance to the actual appearance of the historical Bahram remains, of course, a matter of conjecture.

Regarding his temperament and personal habits, we are largely dependent upon later literary sources of questionable reliability. The tenth-century compendium Mujmal al-Tawarikh wa’l-Qisas characterizes Bahram as “stern in countenance but just in judgment, fond of the chase yet not neglectful of affairs of state.” The Shahnameh of Ferdowsi, that magisterial epic composed in the Islamic period, portrays Bahram I as a monarch of moderate disposition—neither possessed of the martial brilliance of his father nor the decadence attributed to certain later Sasanian rulers.

Archaeological evidence from the royal residence at Bishapur suggests that Bahram maintained the elaborate court ceremonial established by his predecessors. The architectural remains indicate spacious audience halls where the king, seated upon the golden throne, would have received foreign emissaries and native nobility according to a strictly hierarchical protocol.

The paucity of contemporary sources regarding Bahram’s personal life renders speculation about his domestic arrangements hazardous. We know from epigraphic evidence that he had at least one son, the future Bahram II, who would succeed him upon the throne. Other offspring are mentioned in later chronicles, though their historicity remains uncertain.

Rock Relief at Bishapur

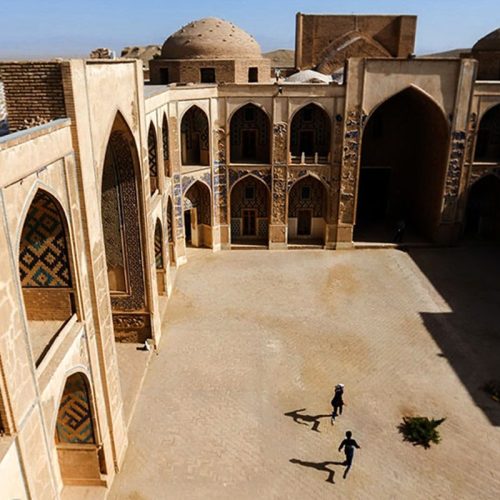

Among the most significant material remains from Bahram’s reign is the rock relief carved into the cliff face at Bishapur in Fars province. This monumental sculpture, executed in the grand tradition established by Darius I and revived by the early Sasanians, constitutes a visual assertion of royal legitimacy and divine favor.

The relief depicts Bahram receiving the diadem of kingship from the hands of Ahura Mazda, represented in anthropomorphic form. The king and the deity stand facing one another, with Bahram’s right hand extended to receive the barsom bundle—symbol of royal authority—while with his left hand he grasps the cydaris (royal diadem). Flanking this central scene are various courtiers and officials, arranged according to their hierarchical importance.

The iconography of this relief is pregnant with political significance. By portraying the king in direct communion with the supreme deity of Zoroastrianism, the sculpture visually articulates the theocratic conception of kingship that characterized Bahram’s reign. Moreover, the absence of martial imagery—in contrast to the triumphal reliefs of Shapur I, which glorify his victories over Roman emperors—reflects the primarily internal focus of Bahram’s governance.

Stylistically, the Bishapur relief exhibits the characteristic features of early Sasanian art: frontality, hieratic composition, and emphasis on symbolic rather than naturalistic representation. The technical execution is of high quality, though perhaps lacking the innovative dynamism evident in the reliefs of Shapur I at the same site.

An inscription in Pahlavi script accompanies the relief, though weathering has rendered portions of it illegible. The decipherable sections proclaim Bahram as “the Mazda-worshipping divine Bahram, King of Kings of Iran and An-Iran, whose image is from the gods, son of the Mazda-worshipping divine Shapur, King of Kings.”

Legacy and Historical Assessment

The historical significance of Bahram I’s reign extends far beyond its brief chronological compass. Through his religious policies, particularly the elevation of Zoroastrianism to quasi-official status and the persecution of Manichaeism, Bahram established precedents that would shape the subsequent development of the Sasanian polity.

The institutionalization of the Zoroastrian priesthood within the apparatus of state created a power structure that would endure, with various modifications, until the Islamic conquest four centuries later. The collaboration between throne and altar inaugurated under Bahram’s auspices would reach its apotheosis during the reign of Khosrow I, when the Zoroastrian hierocracy attained unprecedented influence in matters both spiritual and temporal.

Paradoxically, Bahram’s attempt to extirpate Manichaeism from his dominions contributed to the global dissemination of this dualistic faith. Fleeing persecution within Iran, Manichaean missionaries carried their prophet’s message westward into the Roman Empire and eastward along the Silk Road, establishing communities as far afield as Egypt and China. Thus, an action intended to foster religious uniformity within the Iranian realm inadvertently facilitated the propagation of religious diversity beyond its borders.

In the broader sweep of Sasanian history, Bahram’s reign represents a pivotal transition from the expansionist policies of Shapur I to the more internalist orientation that would characterize much of the dynasty’s middle period. The emphasis on religious orthodoxy, administrative centralization, and cultural consolidation established under Bahram would, with various modifications, inform the governance of his successors for generations to come.

The traditional historiography has tended to regard Bahram as a relatively minor figure overshadowed by his illustrious predecessor and certain of his successors, particularly Shapur II and Khosrow I. This assessment, predicated primarily upon the brevity of his reign and the absence of spectacular military achievements, fails to appreciate the profound structural changes implemented during his tenure—changes that would shape the Sasanian state for centuries thereafter.

A more nuanced evaluation would recognize in Bahram I a monarch of considerable political acumen who, recognizing the limitations imposed by circumstance, eschewed the perilous path of imperial overextension in favor of internal consolidation. The religious policies implemented during his reign, however controversial from a modern pluralistic perspective, were instrumental in forging the distinctive Sasanian synthesis of political and religious authority that would endure until the Islamic conquest.

The foregoing analysis has endeavored to illuminate the manifold aspects of Bahram I’s reign through a critical engagement with the available sources, both textual and material. From this examination emerge the lineaments of a sovereign who, though reigning for but a brief interval, nonetheless exercised a profound influence upon the subsequent development of the Sasanian state.

The traditional narrative, which has often relegated Bahram to the status of a mere transitional figure between more illustrious monarchs, fails to appreciate the significance of the institutional innovations implemented during his reign. The formalization of Zoroastrianism’s role within the state apparatus, the persecution of heterodox religious movements, and the careful maintenance of geopolitical equilibrium all testify to a coherent governance strategy rather than mere opportunistic reaction to immediate circumstances.

If Bahram lacks the martial glory of his father, Shapur I, or the administrative brilliance attributed to later sovereigns such as Khosrow I, he nonetheless merits recognition as a ruler who, perceiving the exigencies of his historical moment, charted a course that would influence the trajectory of Iranian civilization for generations to come.

In our contemporary reassessment of the Sasanian period—a reassessment increasingly informed by archaeological discoveries and more critical approaches to textual sources—the significance of Bahram I’s reign has gradually emerged from the obscurity to which earlier historiographical traditions had consigned it. It is hoped that the present discourse may contribute, in however modest a fashion, to this ongoing reevaluation of a monarch whose historical importance belies the brevity of his reign.

In the final analysis, Bahram I stands as a testament to the capacity of seemingly minor historical actors to effect profound structural changes whose consequences reverberate long after their earthly sojourn has concluded. In this respect, his reign offers a salutary reminder that historical significance is measured not merely in the duration of one’s rule or the extent of one’s conquests, but in the enduring impact of one’s policies upon the institutional fabric of society.

Professor Daryoush Farrokhzad is the author of “Theological Kingship: Religion and Politics in Sasanian Iran” and serves as Director of the Center for Pre-Islamic Iranian Studies at the University of Tehran.