By Dr. Fatemeh Ahmadi Professor of Textile History and Cultural Studies University of Tabriz

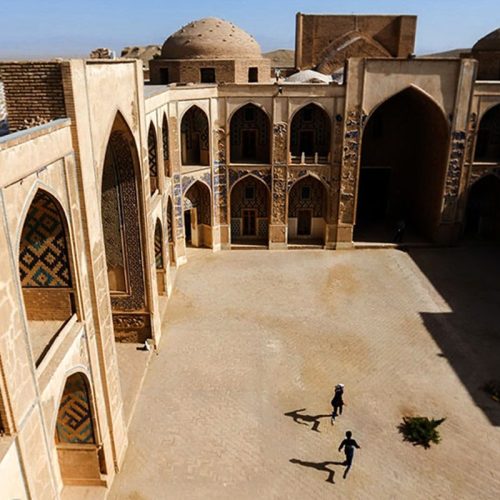

In the narrow, winding alleys of Tabriz’s historic bazaar, where the echoes of centuries of commerce still resonate through ancient brick archways, I first encountered the mesmerizing art of batik printing as a young girl. My grandmother, a master of traditional textile arts, would lead me by the hand through the labyrinthine passages to visit the workshops where artisans transformed plain white fabric into intricate masterpieces through a process that seemed nothing short of magical to my young eyes. Today, as a historian specializing in the textile traditions of Eastern Azerbaijan, I find myself returning to these same alleys, now with the eyes of both a scholar and a keeper of our cultural heritage.

The story of batik in Eastern Azerbaijan is not merely a chapter in our textile history; it is a living testament to our region’s position at the crossroads of the ancient Silk Road, where Persian, Turkish, and Central Asian influences merged to create something uniquely Azerbaijani. As I write this piece, I can smell the distinct aroma of melted wax that still permeates the traditional workshops, a scent that has remained unchanged for generations.

Origins and Evolution

Our region’s relationship with batik printing stretches back centuries, though pinpointing an exact date of introduction proves challenging. Through my research in the provincial archives and countless interviews with elderly artisans, I’ve pieced together a narrative that suggests batik techniques first arrived in Eastern Azerbaijan through trading caravans from Java and India in the 16th century. However, what makes our regional batik tradition distinctive is how local artisans adapted these imported techniques to express our own aesthetic sensibilities and cultural motifs.

I remember sitting with Ustad Mohammad Tabrizi, now in his nineties, who shared with me his family’s batik printing legacy spanning six generations. “We don’t just make patterns,” he told me, his weathered hands tracing invisible designs in the air, “we tell stories through our motifs. Every curve, every color speaks of our land, our people, our history.” His words perfectly encapsulate how Eastern Azerbaijan’s batik tradition has evolved into a unique art form that serves as both a practical craft and a medium for cultural expression.

The Technical Mastery

The process of batik printing in our region has always been characterized by its technical sophistication and attention to detail. Unlike some other regional variations, Eastern Azerbaijan’s batik is distinguished by its use of multiple wax applications and a complex color palette that often includes seven or more distinct hues – a technique I’ve documented extensively in my field research across the province.

The traditional process begins with the preparation of the fabric, typically fine cotton or silk, though historically, wool was also common in our colder climate. The fabric is first treated with a mordant, often derived from local pomegranate rinds – a technique I learned was unique to our region during my comparative studies with Central Asian batik traditions. This preparation ensures the vibrant colors that are characteristic of Azerbaijani batik will remain fast and true for generations.

The wax application process itself is where the true artistry emerges. Our local artisans use a mixture of beeswax and paraffin, carefully balanced to achieve the perfect crack effect (or “veining” as we call it in Azeri) that gives our batik its distinctive appearance. I’ve spent countless hours observing master artisans like Fatima Khanum, whose workshop in the old quarter of Tabriz has been producing batik for over sixty years. Her precision with the canting tool, passed down through generations, demonstrates a level of skill that takes decades to master.

Motifs and Meanings

What truly sets Eastern Azerbaijan’s batik tradition apart is its unique vocabulary of motifs. Through my research, I’ve identified several distinct categories of designs that are specific to our region. The “Arabesques of Tabriz” pattern, for instance, combines traditional Islamic geometric patterns with stylized representations of local flora. These designs tell stories of our region’s rich historical tapestry – where Persian, Turkish, and Islamic influences have merged over centuries.

During my field research in the villages surrounding Mount Sahand, I discovered how local batik artists incorporated motifs inspired by the mountain’s changing seasons into their work. The “Sahand Snowflake” pattern, as I’ve termed it in my academic publications, is a perfect example of how our artisans translate natural phenomena into abstract geometric designs.

Cultural Significance and Social Impact

The significance of batik in Eastern Azerbaijan extends far beyond its aesthetic value. Throughout my career, I’ve observed how this art form has served as a crucial source of economic empowerment, particularly for women in rural communities. In the village of Osku, I worked with a cooperative of female batik artists who have successfully maintained their families’ financial independence through their craft while preserving traditional techniques.

The social fabric of our communities has long been strengthened by the collaborative nature of batik production. In traditional workshops, knowledge is passed down not just through formal apprenticeships but through a complex system of social relationships. I’ve documented how these workshops often serve as important centers for community gathering and cultural preservation, where stories are shared, marriages are arranged, and business deals are struck – all while the rhythmic sound of wax application continues in the background.

Contemporary Challenges and Adaptations

As someone who has dedicated their life to studying and preserving this art form, I cannot ignore the challenges facing Eastern Azerbaijan’s batik tradition in the modern era. The rise of machine-printed textiles and changing consumer preferences has put pressure on traditional artisans to adapt or risk disappearing entirely. However, what I’ve observed over the past two decades gives me hope.

A new generation of artists is emerging, ones who respect tradition while embracing innovation. During my recent visits to workshops in Tabriz, I’ve seen young artisans experimenting with contemporary designs while maintaining traditional techniques. Some have successfully incorporated modern themes into their work, creating pieces that speak to both past and present. The inclusion of social and political commentary in their motifs demonstrates how batik continues to serve as a medium for cultural expression and social discourse.

Environmental Considerations

One aspect of our batik tradition that has gained renewed relevance is its environmental sustainability. Through my research into historical production methods, I’ve discovered that many traditional practices were inherently eco-friendly. The use of natural dyes, locally sourced materials, and traditional waste management techniques offers valuable lessons for contemporary sustainable textile production.

Working with several workshops in the region, I’ve helped document and revive these environmentally conscious practices. The recent establishment of a natural dye garden at the University of Tabriz, where I teach, serves both as a research facility and a source of traditional dyestuffs for local artisans. This initiative has helped bridge the gap between academic research and practical application while promoting sustainable production methods.

The Future of Azerbaijani Batik

As I reflect on the future of batik in Eastern Azerbaijan, I am filled with both concern and optimism. The challenges are significant – from economic pressures to changing social patterns – but the resilience I’ve witnessed throughout my career gives me hope. The art form has survived centuries of political upheaval, economic changes, and social transformation, always adapting while maintaining its essential character.

In my role as both scholar and advocate, I’ve worked to establish programs that connect master artisans with young apprentices, ensuring the continuation of traditional knowledge. The recent inclusion of Eastern Azerbaijan’s batik tradition in UNESCO’s tentative list of intangible cultural heritage (a nomination I had the honor of helping prepare) has brought renewed attention and support to this art form.

Personal Reflections

As I conclude this piece, I find myself back in the bazaar where my journey with batik began. The workshops may be fewer now, but they remain vibrant centers of creativity and cultural preservation. The smell of wax still fills the air, and the sound of quiet conversation still mingles with the tap-tap of canting tools against fabric.

My grandmother, who first introduced me to this world, used to say that every piece of batik carries within it the stories of our people. As I watch a new generation of artisans at work, I see the truth in her words. Each piece they create adds another chapter to our region’s rich cultural narrative, a narrative I’ve been privileged to study and share throughout my career.

The story of batik in Eastern Azerbaijan is far from over. It continues to evolve, adapting to new circumstances while maintaining its connection to our past. As both a scholar and a daughter of this land, I remain committed to ensuring that this vital part of our cultural heritage not only survives but thrives in the years to come.

In the end, perhaps that is what makes our batik tradition truly special – its ability to remain relevant and meaningful while honoring the wisdom of generations past. It is a living art form that continues to tell our stories, preserve our heritage, and connect us to our identity as people of Eastern Azerbaijan.

About the Author: Dr. Fatemeh Ahmadi is a leading authority on the textile traditions of Eastern Azerbaijan. She has published extensively on traditional craft practices and cultural heritage preservation. Her work combines academic research with practical advocacy for traditional artisans. She currently serves as Professor of Textile History and Cultural Studies at the University of Tabriz and directs the Center for Traditional Arts Documentation.