Ta’zieh, a uniquely Iranian form of theater, intertwines the threads of religious devotion, historical narration, and dramatic performance into a rich cultural tapestry. Rooted in the Shia Islamic traditions, Ta’zieh transcends mere storytelling, transforming into a profound ritual that resonates with the collective soul of the Iranian people. This article delves into the origins, evolution, and multifaceted nature of Ta’zieh, exploring its dramatic elements, the role of women, the significance of its spatial and visual components, and its global influence.

The Origins

The origins of Ta’zieh are deeply embedded in the soil of religious mourning and remembrance. Emerging from the grief over the martyrdom of Imam Hussein, the grandson of the Prophet Muhammad, in the Battle of Karbala in 680 AD, Ta’zieh evolved as a medium to convey the tragedy and heroism of this pivotal event. The word “Ta’zieh” itself means “mourning” or “consolation,” encapsulating the essence of this theatrical tradition.

Early Religious Mourning

In the early centuries following the Battle of Karbala, communal mourning rituals began to take shape, particularly during the month of Muharram. These rituals were primarily focused on the profound sorrow and loss felt by the Shia Muslim community over the death of Imam Hussein and his followers. The initial forms of Ta’zieh were simple and somber gatherings where the story of Karbala was recited, often accompanied by weeping and lamentation. This was a way for the community to collectively process their grief and reaffirm their spiritual commitment to the values Imam Hussein stood for.

These early mourning gatherings, known as “majalis” (singular: majlis), served as a foundation for the development of more structured and dramatic forms of expression. The majalis involved recitations of the tragic events of Karbala, poetry, and prayers. Over time, these gatherings became more elaborate, incorporating elements of performance and storytelling. The emotional intensity of these rituals, combined with the communal nature of the mourning, created a fertile ground for the emergence of a distinct theatrical form.

Safavid Era: Institutionalization and Formalization

By the 16th century, during the Safavid dynasty, Ta’zieh had gained significant popularity as a means of religious and cultural expression. The Safavids, who established Shia Islam as the state religion of Iran, played a crucial role in institutionalizing Ta’zieh. They recognized the potential of Ta’zieh to reinforce religious beliefs and promote social cohesion. As a result, they provided state support for the construction of “tekyeh” (plural: tekayat), special venues for the performance of Ta’zieh.

During this period, Ta’zieh began to evolve into a more formalized and sophisticated dramatic form. The performances were no longer confined to simple recitations and lamentations but included elaborate staging, costumes, and choreography. The Safavid rulers patronized poets and playwrights to create scripts for Ta’zieh, which were written in verse and drew heavily from religious texts and historical accounts. These scripts, known as “nesha,” became the backbone of Ta’zieh performances, providing a structured narrative framework.

The Safavid era also saw the development of a distinctive aesthetic for Ta’zieh, characterized by the use of vivid colors, symbolic costumes, and dramatic music. This period marked the transition of Ta’zieh from a communal mourning ritual to a theatrical spectacle that combined elements of drama, music, and visual arts. The performances became grander and more elaborate, attracting large audiences and becoming an integral part of the cultural and religious life of the community.

Qajar Era: Flourishing and Popularization

The Qajar dynasty, which ruled Iran from the late 18th to the early 20th century, witnessed the flourishing and popularization of Ta’zieh. The Qajar rulers, like their Safavid predecessors, were ardent supporters of Shia Islam and saw Ta’zieh as a powerful tool for religious and political purposes. They invested heavily in the construction of grand tekayat and supported the organization of elaborate Ta’zieh performances.

During the Qajar era, Ta’zieh reached new heights of popularity and artistic sophistication. The performances became more elaborate and theatrical, incorporating intricate sets, elaborate costumes, and complex choreography. The tekayat were often designed with architectural elements that enhanced the dramatic effect of the performances, such as raised platforms, balconies, and special lighting.

The Qajar period also saw the emergence of professional Ta’zieh troupes, consisting of skilled actors, musicians, and directors. These troupes traveled across the country, performing in urban and rural areas and spreading the popularity of Ta’zieh. The performances were no longer limited to religious occasions but became a popular form of entertainment, attracting diverse audiences from all walks of life.

The Qajar rulers themselves often attended Ta’zieh performances, and the royal patronage added to the prestige and popularity of the art form. The performances became a platform for the expression of social and political themes, reflecting the concerns and aspirations of the society. Ta’zieh also began to incorporate elements of secular drama, blending religious and cultural narratives in a unique and innovative way.

Ta’zieh and Its Oral Tradition

One of the defining features of Ta’zieh is its strong oral tradition. In the early stages of its development, the stories and scripts of Ta’zieh were passed down orally from one generation to the next. This oral transmission ensured that the performances remained dynamic and adaptable, allowing for variations and improvisations based on the local context and the audience’s preferences.

The oral tradition also played a crucial role in preserving the authenticity and integrity of Ta’zieh. The recitations and performances were often memorized by heart, and the performers were trained to deliver the lines with the appropriate emotional intensity and reverence. The oral tradition fostered a deep sense of connection and continuity between the past and the present, allowing the community to relive the events of Karbala and reaffirm their spiritual and cultural identity.

Ta’zieh as a Reflection of Socio-Political Contexts

Throughout its history, Ta’zieh has been closely intertwined with the socio-political context of Iran. The performances often reflect the contemporary concerns and issues of the society, providing a platform for the expression of social and political commentary. During times of political upheaval and social change, Ta’zieh has served as a medium for the articulation of collective grievances and aspirations.

For example, during the Constitutional Revolution of the early 20th century, Ta’zieh performances incorporated themes of justice, freedom, and resistance, reflecting the revolutionary fervor of the time. Similarly, during the Islamic Revolution of 1979, Ta’zieh became a symbol of resistance and martyrdom, resonating with the revolutionary ideals and sentiments.

The adaptability of Ta’zieh to different socio-political contexts is a testament to its enduring relevance and vitality. It has the capacity to evolve and respond to the changing needs and aspirations of the community, while retaining its core religious and cultural essence.

Ta’zieh in Iranian Culture

Ta’zieh is not just a form of entertainment; it is a cultural phenomenon deeply ingrained in the Iranian psyche. It serves as a conduit for the expression of collective grief, religious devotion, and moral values. The annual performances during Muharram attract large audiences, who participate not merely as spectators but as active participants in the ritual of mourning.

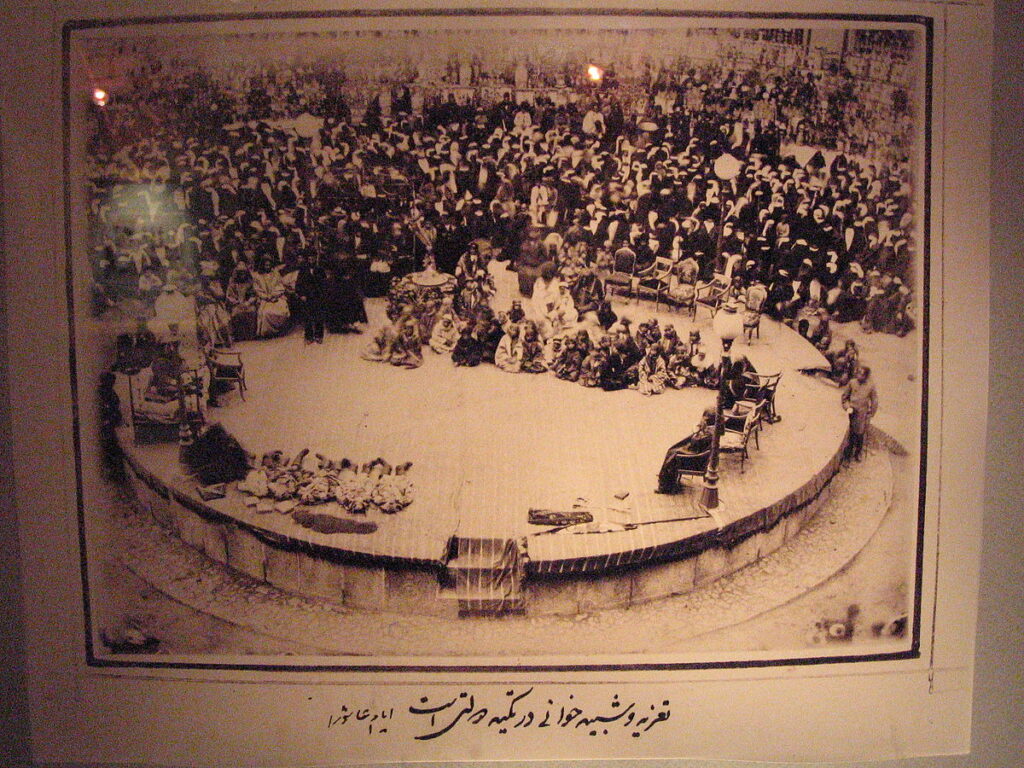

The performance of Ta’zieh is a communal event that brings together people from all walks of life. It is often staged in public spaces such as town squares, where temporary structures known as “tekyeh” are erected to accommodate the audience and performers. These spaces become sanctified grounds, where the boundaries between the past and present, the real and the performative, blur.

The Development of Ta’zieh as a Dramatic Form

Ta’zieh’s development into a dramatic form involved the synthesis of various elements, including poetry, music, and visual arts. The scripts of Ta’zieh, known as “nesha,” are written in verse and draw heavily from religious texts and historical accounts. These scripts are rich in metaphor and allegory, elevating the narrative to a spiritual plane.

The dramatic structure of Ta’zieh is distinctive, with a clear division between the protagonists and antagonists. The protagonists, representing the martyrs and their supporters, are typically dressed in green, symbolizing purity and righteousness. The antagonists, representing the oppressors, wear red, denoting their evil nature. This use of color is a powerful visual tool that reinforces the moral dichotomy central to Ta’zieh.

Music plays a crucial role in Ta’zieh, with different instruments and melodies employed to evoke various emotions. The “santur,” a type of hammered dulcimer, and the “nay,” a reed flute, are commonly used to create an atmosphere of sorrow and reverence. The rhythmic chants and lamentations of the performers further enhance the emotional intensity of the performance.

Guriz or Flashbacks in Ta’zieh

A distinctive feature of Ta’zieh is the use of “guriz,” or flashbacks, which serve to provide historical context and deepen the emotional impact of the narrative. These flashbacks often depict earlier events in the lives of the protagonists, highlighting their virtues and the injustices they endured. The seamless integration of these flashbacks into the main narrative creates a multi-layered storytelling experience that engages the audience on multiple levels.

Guriz also serves a didactic purpose, reinforcing the moral and religious lessons embedded in the story. By juxtaposing past and present, Ta’zieh underscores the timeless nature of its themes and the enduring relevance of its message.

Decline of Ta’zieh Plays in Iran

Despite its deep cultural roots and historical significance, Ta’zieh has faced periods of decline, particularly in the modern era. The advent of new forms of entertainment, changing social dynamics, and political pressures have all contributed to the waning popularity of Ta’zieh.

In the early 20th century, the rise of cinema and other Western cultural influences began to overshadow traditional forms of theater, including Ta’zieh. The Pahlavi regime’s modernization policies further marginalized Ta’zieh, as they sought to promote a secular, Westernized image of Iran. Ta’zieh performances were restricted, and many tekyeh were demolished or repurposed.

However, the Islamic Revolution of 1979 brought a resurgence of interest in Ta’zieh, as the new regime sought to revive traditional religious and cultural practices. Despite this revival, Ta’zieh continues to face challenges in a rapidly changing society. Efforts to preserve and promote Ta’zieh are ongoing, with cultural organizations and enthusiasts striving to keep this unique art form alive.

Women in Ta’zieh

The role of women in Ta’zieh is a complex and evolving aspect of this tradition. Historically, women were largely excluded from performing in Ta’zieh, due to religious and social norms that restricted their public visibility. Female characters were typically portrayed by young boys or effeminate men, a practice that added a layer of symbolic ambiguity to the performances.

In recent years, there has been a growing movement to involve women in Ta’zieh, both as performers and as creators. Women have begun to take on roles traditionally reserved for men, challenging long-standing gender norms and bringing new perspectives to the art form. This shift reflects broader changes in Iranian society, where women are increasingly asserting their presence in various cultural and social spheres.

The inclusion of women in Ta’zieh has sparked debates and controversies, with some viewing it as a necessary step towards gender equality, while others see it as a departure from tradition. Regardless of these debates, the presence of women in Ta’zieh is undeniably transforming the landscape of this ancient art form.

Importance of the Space

The spatial dynamics of Ta’zieh are integral to its impact and meaning. The tekyeh, where Ta’zieh is performed, is not just a physical structure but a symbolic space that represents the battlefield of Karbala and the spiritual realm of the martyrs. The circular or semi-circular arrangement of the audience around the performance area creates a sense of intimacy and participation, drawing the spectators into the heart of the drama.

The use of space in Ta’zieh is highly ritualistic, with specific areas designated for different actions and symbols. The “makhzan,” a small structure at the center of the tekyeh, represents the tomb of Imam Hussein and serves as a focal point for the performance. The movements of the performers around the makhzan are carefully choreographed to convey the unfolding of the narrative and the spiritual journey of the characters.

The spatial arrangement also facilitates the interaction between the performers and the audience. The boundaries between the stage and the spectators are fluid, with performers often moving among the audience, addressing them directly, and involving them in the action. This blurring of boundaries enhances the emotional and immersive experience of Ta’zieh, reinforcing its communal and participatory nature.

Costumes and Character Distinctions

Costumes in Ta’zieh are not merely decorative but serve as powerful symbols that convey the moral and spiritual essence of the characters. The use of color, fabric, and accessories is carefully chosen to reflect the virtues and vices of the protagonists and antagonists.

The protagonists, representing the martyrs and their followers, are typically dressed in white, green, or blue, colors that symbolize purity, piety, and loyalty. Their costumes are often adorned with simple, elegant details that emphasize their noble and righteous nature. In contrast, the antagonists, representing the oppressors, wear red or black, colors associated with evil, deceit, and aggression. Their costumes are more elaborate and ornate, reflecting their worldly power and moral corruption.

The use of masks and makeup further distinguishes the characters and adds a layer of theatricality to the performance. Masks are often used to portray supernatural beings or to enhance the dramatic impact of certain characters. Makeup is applied to exaggerate facial features, emphasizing the emotional states and moral qualities of the characters.

The visual distinction between the characters is not just a matter of aesthetics but serves to reinforce the moral dichotomy at the heart of Ta’zieh. It allows the audience to instantly recognize and empathize with the protagonists, while condemning the actions of the antagonists.

Animals in the Tradition

Animals play a significant role in Ta’zieh, both as symbolic elements and as active participants in the performance. The inclusion of animals such as horses and camels adds a layer of realism and authenticity to the portrayal of historical events, particularly the Battle of Karbala.

Horses are especially important in Ta’zieh, representing the valor and nobility of the martyrs. The horse of Imam Hussein, known as Zuljanah, is a revered figure in Ta’zieh, symbolizing loyalty and sacrifice. The portrayal of Zuljanah’s grief and loyalty after the martyrdom of Imam Hussein is a poignant moment in the performance, eliciting deep emotions from the audience.

Camels are also used to represent the journey of the martyrs and their families, adding to the historical and cultural authenticity of the performance. The use of live animals requires careful handling and training, adding a layer of complexity to the staging of Ta’zieh.

The presence of animals in Ta’zieh serves to bridge the human and natural worlds, emphasizing the universality of the themes of sacrifice, loyalty, and justice. It also enhances the sensory experience of the performance, creating a vivid and immersive spectacle.

Ta’zieh Around the World

Ta’zieh, though rooted in Iranian culture, has transcended national boundaries and gained recognition as a unique and powerful form of theater around the world. International interest in Ta’zieh has grown in recent decades, with performances being staged in various countries and academic studies exploring its significance and impact.

In the late 20th and early 21st centuries, Ta’zieh was introduced to Western audiences through festivals, academic conferences, and cultural exchanges. These international performances often involve collaboration between Iranian and foreign artists, resulting in innovative interpretations and adaptations of the traditional form.

The global recognition of Ta’zieh has also led to its inclusion in UNESCO’s Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, highlighting its significance as a cultural and artistic treasure. This recognition has spurred efforts to preserve and promote Ta’zieh, both in Iran and internationally.

The universal themes of Ta’zieh, such as the struggle between good and evil, the sacrifice for a noble cause, and the quest for justice, resonate with audiences across different cultures and backgrounds. The emotional and spiritual depth of Ta’zieh transcends linguistic and cultural barriers, making it a compelling and transformative experience for audiences worldwide.

Ta’zieh is a testament to the enduring power of storytelling and the human spirit’s capacity for empathy, devotion, and resilience. As a unique blend of religious ritual, dramatic art, and cultural expression, Ta’zieh continues to captivate and inspire, reflecting the rich tapestry of Iranian culture and its profound spiritual heritage.

Despite the challenges and changes over the centuries, Ta’zieh remains a vibrant and vital part of Iran’s cultural landscape. Its evolution, from its origins in religious mourning to its recognition as a global cultural treasure, is a testament to its enduring relevance and impact.

As we reflect on the multifaceted nature of Ta’zieh, we are reminded of the timeless themes of sacrifice, justice, and the eternal struggle between good and evil. Through the lens of Ta’zieh, we gain a deeper understanding of the Iranian soul and the universal human experience, finding inspiration and meaning in the shared stories of our past and present.