By Dr. Farzaneh Rahimi Center for Iranian Literary Studies, University of Nakhchivan

In the tapestry of medieval Persian literature, few figures shine as brilliantly yet remain as enigmatic as Mahsati Ganjavi, a remarkable female poet whose verses challenged the conventions of her time. As one of the earliest known female composers of ruba’iyat (quatrains), Mahsati carved out a unique place in Persian literary history, demonstrating that poetic genius knows no gender. Through her bold verses and unconventional life, she embodied the progressive spirit that occasionally flickered through medieval Islamic society, particularly in the cultural centers of Greater Iran.

A Life Shrouded in Poetic Mystery

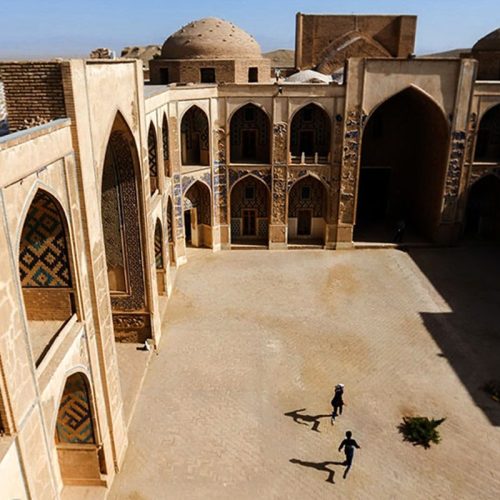

The biographical details of Mahsati’s life, like many medieval Persian figures, are interwoven with legend and literary anecdote. Most scholars place her life in the late 11th to mid-12th century CE, during the Seljuk period, though exact dates remain contested. Born in Ganja (in present-day Azerbaijan), she emerged from a city already renowned for its cultural sophistication and literary output. The very name “Mahsati” presents an etymological puzzle – some suggest it derives from “Mah” (moon) and “Sati” (lady), while others propose it comes from “Mahasti” (greater than the moon). Such linguistic ambiguity seems fitting for a poet whose life story combines historical fact with romantic legend.

Contemporary sources suggest Mahsati received an education unusual for women of her era, gaining proficiency in Arabic, astronomy, and the Islamic sciences alongside her native Persian literary traditions. Her intellectual achievements hint at a privileged background, though the exact nature of her family’s status remains unclear. What is certain is that she eventually found her way to the Seljuk court, where her quick wit and poetic talent caught the attention of Sultan Sanjar, who appointed her as his court poet – a position traditionally reserved for men.

The historical record presents Mahsati as a woman of remarkable independence and intellectual prowess. Anecdotes describe her engaging in poetic duels with male counterparts, often emerging victorious through her sharp intellect and masterful command of improvised verse. These accounts, while potentially embellished, reflect a cultural milieu where female intellectual achievement, though rare, was not entirely impossible.

Poetic Innovation and Artistic Legacy

Mahsati’s most significant contribution to Persian literature lies in her mastery of the ruba’i form. While she did not invent this quatrain structure, she was among the first to elevate it to new heights of emotional and philosophical complexity. Her ruba’iyat demonstrate a remarkable range, from deeply personal expressions of love and desire to philosophical musings on existence and fate.

Consider this example, which showcases her characteristic blend of sensuality and wisdom:

The moon casts silver on the garden wall, While wine-cup glimmers, ready for its fall. Seize now this moment, sweet and fleet as dew – Tomorrow’s dawn may never come to call.

This quatrain exemplifies Mahsati’s ability to weave together multiple thematic threads – the ephemeral nature of beauty, the urgency of present joy, and the uncertainty of future promises. Her verses often challenge the rigid moral strictures of her time, advocating for a more nuanced understanding of human nature and desire.

Mahsati’s poetry is distinguished by its immediacy and emotional authenticity. Unlike many of her contemporaries who wrote in highly formalized styles, she often drew inspiration from real-life experiences and observations. Her verses about love, both sacred and profane, reveal a deep understanding of human nature and the complexities of desire. She wrote with remarkable candor about themes that many of her male contemporaries approached only through allegory and metaphor.

Another distinctive aspect of Mahsati’s work is her treatment of the natural world. Her imagery often draws from the gardens, moonlight, and changing seasons of her native Azerbaijan, but transforms these familiar elements into powerful metaphors for human experience:

The spring wind whispers secrets to the rose, While morning dew like scattered pearl-drops shows. Yet briefer than this garden’s fleeting bloom Is love’s sweet season, as time’s river flows.

Cultural Context and Historical Significance

To fully appreciate Mahsati’s achievements, we must understand the cultural context in which she worked. The Seljuk period, despite its political turbulence, witnessed a remarkable flowering of Persian literature and art. Yet this cultural renaissance occurred within a society that generally relegated women to the domestic sphere. Mahsati’s success as a court poet represents a rare breach in these gender boundaries.

Her position at Sultan Sanjar’s court was both a privilege and a challenge. While it provided her with patronage and protection, it also exposed her to the political intrigues and religious conservatives’ criticism that were inevitable in court life. Several historical sources suggest she faced opposition from religious authorities who disapproved of both her poetry’s content and her public role as a female artist.

The fact that Mahsati’s works survived despite these challenges speaks to their intrinsic value and the protection afforded by her royal patronage. Her poetry appears in several major medieval anthologies, suggesting that even conservative scholars could not entirely ignore her contributions to Persian literature.

Influence on Persian Literary Tradition

Mahsati’s influence on Persian literature extends far beyond her own era. Her innovative approach to the ruba’i form influenced later poets, both male and female. Her work demonstrated that the quatrain could accommodate complex philosophical ideas while maintaining emotional authenticity and linguistic precision.

Moreover, her success as a female poet created a precedent that later generations of women writers could reference. While female poets remained rare in Persian literature for centuries after Mahsati, her example proved that gender need not be a barrier to literary achievement. The very existence of her work challenged the notion that poetry was exclusively a male domain.

Modern Reception and Feminist Interpretations

Contemporary scholars, particularly those interested in women’s literary history, have found in Mahsati’s work a valuable window into medieval Persian gender dynamics. Her poetry reveals both the possibilities and limitations that existed for educated women in medieval Islamic society. While her success demonstrates that talent could sometimes transcend gender barriers, the exceptionality of her case highlights how rare such opportunities were.

Feminist scholars have particularly noted how Mahsati’s verses often subtly subvert traditional gender roles. In many of her love poems, for instance, the female voice is active rather than passive, expressing desire rather than merely being its object. This representation challenged medieval conventions and continues to resonate with modern readers.

Critical Assessment and Scholarly Debates

Modern scholarship on Mahsati faces several challenges. First is the question of attribution – as with many medieval poets, some verses attributed to her may be later additions to her corpus. Scholars continue to debate which poems can be confidently assigned to her authorship.

Another area of scholarly discussion concerns the relationship between Mahsati’s historical person and her literary persona. The romantic legends that grew up around her figure – including stories of love affairs with younger poets – may reflect cultural anxieties about female artistic achievement as much as historical fact.

Yet these uncertainties should not overshadow Mahsati’s genuine achievements. The core body of work attributed to her displays a consistent artistic vision and technical mastery that confirms her place among the significant poets of medieval Persia.

Mahsati’s Relevance Today

In our contemporary world, where questions of gender equality and artistic freedom remain pressing concerns, Mahsati’s legacy takes on renewed significance. Her life and work demonstrate that artistic excellence can transcend social constraints, while also reminding us how exceptional such achievements were in her time.

For modern Iranian women writers, Mahsati represents a vital link to their literary heritage. Her success in navigating the constraints of her era while producing work of lasting value offers both inspiration and instruction. Her poetry’s emphasis on authentic emotional expression and intellectual independence continues to resonate with contemporary audiences.

Mahsati Ganjavi stands as a remarkable figure in Persian literary history – not merely as a female poet who succeeded in a male-dominated field, but as an artist whose work continues to speak to readers across centuries. Her ruba’iyat demonstrate both technical mastery and emotional depth, while her life story provides evidence that medieval Islamic society, despite its restrictions, could sometimes make room for exceptional talent regardless of gender.

As we continue to uncover and analyze her work, Mahsati’s significance only grows. She represents not just a historical curiosity but a poet whose verses still capture the complexities of human experience and the power of artistic expression. In her bold defiance of conventional limitations and her commitment to authentic artistic expression, Mahsati offers an example that remains relevant and inspiring to this day.

The endurance of her work, surviving centuries of political and social upheaval, testifies to its intrinsic artistic value. As we seek to understand the full breadth of Persian literary history and the contributions of women to world literature, Mahsati’s legacy demands our continued attention and study. Her verses, bridging the centuries with their clarity and power, remind us that true artistic genius knows no boundaries of gender, time, or social convention.