Persian mythology, a rich tapestry of tales and legends, holds a mirror to the soul of an ancient civilization. Rooted in the deep spiritual and cultural heritage of Persia, these myths weave a narrative that explores the cosmos, the struggle between good and evil, and the essence of life and death. This article delves into the myriad aspects of Persian mythology, from its religious background to the famous myths that have transcended time, painting a vivid picture of a world where gods, monsters, and heroes coexisted in an eternal dance of creation and destruction.

Religious Background

In the dawn of Persian civilization, spiritual beliefs were intrinsically linked to the natural world. Early Persians worshipped a pantheon of deities associated with elements like the sun, moon, water, and fire. However, the spiritual landscape of Persia was dramatically transformed with the advent of Zoroastrianism, a religion founded by the prophet Zoroaster (or Zarathustra) around the 6th century BCE.

Zoroastrianism introduced a dualistic cosmology that profoundly influenced Persian mythology. Central to this belief system was the eternal battle between Ahura Mazda, the wise and benevolent creator, and Ahriman (Angra Mainyu), the malevolent spirit of chaos and destruction. This dualism is a cornerstone of Zoroastrian thought, encapsulating the perpetual struggle between good and evil, order and disorder.

The sacred texts of Zoroastrianism, the Avesta, and later the Pahlavi literature, provided a framework for understanding the universe, morality, and human existence. These texts not only offered religious guidance but also enriched Persian mythology with stories of divine creation, cosmic battles, and eschatological visions.

The Zoroastrian emphasis on moral righteousness (asha) and the constant fight against falsehood (druj) permeated the mythological narratives. The religion’s profound impact can be seen in the way Persian myths personify abstract concepts, creating a vivid and dynamic mythology that reflects the ethical and philosophical underpinnings of Zoroastrianism.

Good and Evil

In Persian mythology, the dichotomy of good and evil is more than a moral distinction; it is a fundamental principle of existence. This duality is vividly personified by Ahura Mazda and Ahriman, whose cosmic struggle symbolizes the eternal conflict between light and darkness.

Ahura Mazda, the supreme god, embodies goodness, wisdom, and order. He is the creator of the universe and the guardian of asha, the divine order that sustains life. His attributes include truth, justice, and benevolence, and he is often depicted as a radiant figure, illuminating the world with his divine light.

In stark contrast stands Ahriman, the embodiment of druj (deceit) and the source of all evil. Ahriman’s domain is one of darkness, chaos, and destruction. He is a master of lies and corruption, constantly seeking to undermine Ahura Mazda’s creation and spread misery and disorder.

The conflict between these two forces is not merely an abstract concept but a cosmic drama played out in the myths and legends of Persia. This struggle is mirrored in the human realm, where individuals are called upon to choose sides and align themselves with either the forces of good or evil. The righteous are those who uphold asha, living lives of honesty, integrity, and compassion, while the followers of druj are marked by deceit, violence, and selfishness.

The ultimate victory of Ahura Mazda over Ahriman is a central theme in Persian mythology, reflecting a deep-seated belief in the triumph of good over evil. This eschatological vision promises a future where the world is purified, and evil is vanquished, leading to the final restoration of order and harmony.

Development of Persian Mythology

The development of Persian mythology is a journey through time, influenced by various dynasties, cultures, and historical events. From the ancient Elamites to the rise and fall of the Achaemenid, Parthian, and Sassanian empires, each era contributed to the rich tapestry of Persian myths.

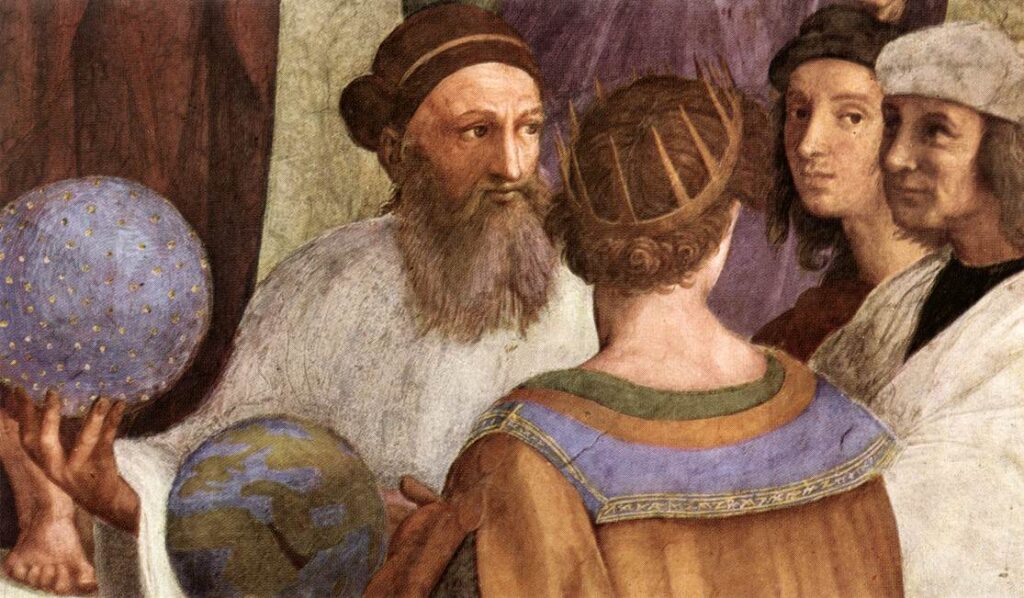

The Achaemenid Empire (550–330 BCE), founded by Cyrus the Great, was a period of significant mythological evolution. The empire’s vast expanse brought Persian culture into contact with numerous other civilizations, including the Greeks, Egyptians, and Babylonians. These interactions facilitated a cultural exchange that enriched Persian mythology with new themes and motifs.

During the Parthian period (247 BCE – 224 CE), Persian mythology absorbed elements from Hellenistic culture. The Parthians, who were known for their eclecticism, integrated Greek gods and heroes into their own pantheon, creating a syncretic mythology that reflected the diverse influences of the time.

The Sassanian Empire (224–651 CE) marked a renaissance of Persian culture and Zoroastrianism. Under Sassanian rule, Zoroastrianism was revitalized and institutionalized, leading to a resurgence of mythological narratives centered around Zoroastrian cosmology and ethics. This period saw the compilation and preservation of many ancient myths in texts such as the Bundahishn and the Denkard.

Despite the Islamic conquest of Persia in the 7th century, Persian mythology continued to evolve. The new Islamic rulers, while promoting their own religious beliefs, also showed respect for Persian culture and literature. As a result, many Persian myths were preserved and even incorporated into Islamic literature, blending pre-Islamic and Islamic elements into a unique cultural synthesis.

Overview of the World

In Persian mythology, the world is a carefully structured cosmos, reflecting the intricate balance between order and chaos. This cosmology is rooted in Zoroastrian thought, which envisions the universe as a battleground between the forces of good and evil.

The cosmos is divided into several realms, each with its own significance and inhabitants. At the center of this structure is the earth, which is viewed as a flat disc surrounded by an endless ocean. The earth is divided into seven regions (keshvars), with the central region, Khvaniratha, being the most important and sacred.

Above the earth lies the sky, which is divided into three layers. The lowest layer is the domain of the stars, the middle layer houses the moon, and the highest layer is the realm of the sun. These celestial bodies are not merely astronomical objects but divine entities, each playing a crucial role in maintaining the cosmic order.

Beyond the sky is the realm of the divine, where Ahura Mazda and other gods reside. This is a place of pure light and goodness, untouched by the corrupting influence of Ahriman. It is here that the divine plan for the universe is conceived and directed.

Below the earth lies the underworld, a dark and chaotic place ruled by Ahriman and his minions. This is the realm of the druj, where evil spirits dwell and plot against the forces of good. The underworld is a place of suffering and torment, reflecting the destructive nature of Ahriman and his followers.

The interaction between these realms is a central theme in Persian mythology, with the actions of gods, humans, and demons affecting the balance between order and chaos. The ultimate goal of this cosmic drama is the triumph of Ahura Mazda and the restoration of harmony, culminating in the final renovation of the world (Frashokereti).

Evil Forces

Evil forces in Persian mythology are personified by a host of malevolent entities, each playing a role in the grand scheme of cosmic conflict. At the heart of these evil forces is Ahriman, the arch-nemesis of Ahura Mazda and the embodiment of chaos and destruction.

Ahriman’s primary objective is to undermine Ahura Mazda’s creation and spread druj (falsehood) throughout the universe. To achieve this, he commands an army of demons (daevas) and evil spirits, each specializing in a particular form of corruption and deceit.

One of the most feared demons is Azhi Dahaka (Zahhak), a monstrous serpent with three heads and six eyes. According to legend, Zahhak was once a human king who became corrupted by Ahriman and transformed into a fearsome dragon. His reign of terror symbolizes the destructive power of evil and the corruption of humanity.

Another prominent figure is Angra Mainyu, often considered synonymous with Ahriman. Angra Mainyu leads the forces of darkness and is responsible for creating diseases, lies, and all forms of suffering. His influence is felt in every corner of the world, constantly challenging the forces of good.

Evil forces also include lesser demons and spirits that plague humanity. These entities, known as “dews” or “divs,” cause various afflictions, from physical ailments to moral corruption. They are cunning and relentless, always seeking to lure humans away from the path of righteousness.

Despite their formidable power, these evil forces are ultimately destined for defeat. Persian mythology promises the eventual triumph of good over evil, with Ahura Mazda and his divine allies restoring order and purity to the world. This eschatological vision provides hope and reassurance, emphasizing the moral imperative to resist evil and uphold the principles of truth and justice.

Ahura Mazda and Ahriman

The central figures of Ahura Mazda and Ahriman epitomize the eternal struggle between good and evil in Persian mythology. Their epic confrontation is not only a cosmic battle but also a reflection of the moral choices that define human existence.

Ahura Mazda, known as the “Wise Lord,” is the supreme god of Zoroastrianism and the ultimate source of all that is good. He is the creator of the universe, embodying wisdom, light, and truth. Ahura Mazda’s attributes include omniscience, omnipotence, and benevolence. He is often depicted as a radiant figure, symbolizing the light of wisdom that dispels the darkness of ignorance and evil.

Ahura Mazda’s role is to sustain the cosmic order (asha) and guide humanity towards righteousness. He communicates his will through the Amesha Spentas, a group of divine spirits who represent various aspects of creation and moral virtues. These spirits act as intermediaries between Ahura Mazda and the material world, helping to maintain the balance of the universe.

In stark contrast stands Ahriman (Angra Mainyu), the “Destructive Spirit.” Ahriman is the personification of evil and chaos, constantly seeking to disrupt Ahura Mazda’s creation. He embodies all that is dark, deceitful, and destructive. Ahriman’s influence is felt in the corruption of nature, the spread of diseases, and the moral decay of humanity.

Ahriman’s ultimate goal is to overthrow Ahura Mazda and establish his own reign of chaos. To achieve this, he unleashes an army of demons and evil spirits, each dedicated to spreading druj (falsehood) and undermining asha (truth). Despite his power, Ahriman’s efforts are ultimately futile, as Ahura Mazda’s light and wisdom are destined to prevail.

The dynamic between Ahura Mazda and Ahriman serves as a powerful allegory for the moral struggle faced by individuals. It emphasizes the importance of choosing the path of righteousness, upholding truth, and resisting the temptations of deceit and corruption. The eventual triumph of Ahura Mazda over Ahriman symbolizes the victory of good over evil, offering hope and assurance to those who strive to live virtuous lives.

Myths of Creation and the End of the World

Persian mythology is rich with tales of creation and the end of the world, reflecting the Zoroastrian vision of cosmic cycles and the ultimate triumph of good over evil.

Creation Myths

In the beginning, Ahura Mazda created the universe in a perfect and pure state, known as the realm of asha. This creation unfolded in stages, each bringing forth a new element of the cosmos. First, Ahura Mazda created the sky, a vast dome of pure light. Then came the waters, forming seas and rivers. The third creation was the earth, a flat expanse teeming with life. Next were the plants, covering the earth in greenery, followed by the creation of animals. Finally, Ahura Mazda created humans, bestowing them with the gift of free will and the responsibility to uphold asha.

Ahriman, filled with jealousy and hatred, sought to corrupt Ahura Mazda’s creation. He unleashed his own creations, introducing chaos and destruction into the world. This marked the beginning of the cosmic struggle between good and evil, a battle that would continue until the end of time.

Eschatological Myths

Persian eschatology, or beliefs about the end of the world, centers on the concept of Frashokereti, the final renovation. According to Zoroastrian prophecy, the world will undergo a series of cataclysms before being purified and restored to its original perfection.

At the end of time, a savior figure known as Saoshyant will appear. Saoshyant, born of a virgin mother and the seed of Zoroaster, will lead the forces of good in the final battle against Ahriman and his minions. This apocalyptic confrontation will see the forces of light and darkness clash in a decisive struggle.

Following the defeat of Ahriman, the world will be cleansed through a river of molten metal. The righteous will pass through unharmed, while the wicked will be purified of their sins. This purging fire will eradicate all traces of evil, paving the way for the resurrection of the dead and the restoration of creation.

In the renewed world, Ahura Mazda will reign supreme, and all beings will live in harmony and bliss. The cycle of life and death will be broken, and immortality will be granted to all. This vision of Frashokereti underscores the Zoroastrian belief in the ultimate victory of good over evil and the promise of a perfect, eternal existence.

Mythological History of Iran

The mythological history of Iran is a grand narrative that intertwines with the nation’s rich cultural and historical heritage. It spans from the dawn of creation to the establishment of ancient dynasties, reflecting the values, beliefs, and aspirations of the Persian people.

The earliest period of Persian mythology is marked by the reign of primordial kings and heroes. Figures like Yima (Jamshid), the first man and king, who introduced civilization to humanity, play a crucial role in these ancient tales. Yima’s reign is often depicted as a golden age of prosperity and abundance, a time when humans lived in harmony with nature.

The Pishdadian dynasty, traditionally regarded as the first royal dynasty of Iran, is another significant epoch in Persian mythological history. Kings like Hushang, Tahmuras, and Jamshid are celebrated for their wisdom, bravery, and contributions to society. These rulers are credited with introducing essential cultural and technological advancements, such as agriculture, metalworking, and medicine.

The Kayanian dynasty follows, with legendary kings like Kay Khosrow, Kay Kavus, and Kay Bahman. This period is rich with epic battles, heroic deeds, and divine interventions. The Kayanian kings are often depicted as paragons of virtue and justice, leading their people against the forces of darkness and tyranny.

The mythical history of Iran also includes the tales of Rostam, the greatest hero of Persian mythology. Rostam’s exploits, as recounted in the Shahnameh (Book of Kings) by Ferdowsi, are a cornerstone of Persian cultural identity. His battles against formidable foes, his unwavering loyalty, and his tragic fate encapsulate the essence of heroism and the complexities of human nature.

These mythological narratives, though intertwined with historical events, transcend mere chronicles of the past. They embody the moral and spiritual ideals of the Persian people, serving as a source of inspiration and a testament to the enduring legacy of Persian culture.

Life & Afterlife

Persian mythology offers profound insights into the beliefs about life, death, and the afterlife, reflecting the Zoroastrian worldview that dominated ancient Persia.

Life

Life in Persian mythology is seen as a sacred journey, a test of moral integrity and righteousness. Humans are bestowed with free will, enabling them to choose between the path of asha (truth and order) and druj (falsehood and chaos). This moral duality underscores the importance of individual responsibility and the eternal struggle between good and evil.

The purpose of life is to uphold asha, contributing to the cosmic battle against Ahriman and his forces. By living a righteous life, humans align themselves with Ahura Mazda and help maintain the balance of the universe. This emphasis on ethical conduct and spiritual purity is a central tenet of Zoroastrianism, shaping the Persian understanding of existence.

Afterlife

The concept of the afterlife in Persian mythology is intricately linked to one’s actions in life. Upon death, a person’s soul embarks on a journey to the afterlife, passing through several stages of judgment and purification.

The first stage is the crossing of the Chinvat Bridge, a metaphorical bridge that separates the world of the living from the afterlife. The bridge is guarded by the deity Mithra and the soul’s conscience (Daena). For the righteous, the bridge widens and leads to the House of Song (Garothman), a paradise of eternal bliss where they are united with Ahura Mazda and other divine beings. The House of Song is depicted as a place of light, joy, and harmony, reflecting the reward for a life lived in accordance with asha.

For the wicked, however, the Chinvat Bridge narrows and becomes impassable, leading them to the House of Lies (Drujo Demana), a hellish realm of darkness and suffering. This realm is ruled by Ahriman and inhabited by demons, representing the torment and anguish that await those who succumbed to druj in life.

The final renovation (Frashokereti) promises a universal resurrection and purification. At the end of time, all souls, both good and evil, will be resurrected and judged. The righteous will enter a new, perfect world, while the wicked will be purified of their sins in a river of molten metal, ultimately joining the righteous in the renewed creation.

This vision of the afterlife underscores the Zoroastrian belief in justice, accountability, and the ultimate triumph of good over evil. It offers hope and reassurance, emphasizing the importance of living a virtuous life and the promise of eternal reward for those who uphold asha.

Gods

Persian mythology features a pantheon of gods, each embodying various aspects of creation, morality, and the natural world. These deities play crucial roles in maintaining the cosmic order and guiding humanity.

Ahura Mazda

As the supreme god, Ahura Mazda is the creator and ruler of the universe. He embodies wisdom, light, and truth, overseeing all aspects of existence. Ahura Mazda’s omniscience and omnipotence make him the ultimate source of goodness and the primary opponent of Ahriman.

Amesha Spentas

The Amesha Spentas, or “Holy Immortals,” are divine spirits who assist Ahura Mazda in sustaining the cosmos. Each Amesha Spenta represents a specific aspect of creation and moral virtue. Key figures include:

- Vohu Manah (Good Mind): Represents good thoughts and moral wisdom.

- Asha Vahishta (Best Truth): Embodies truth, order, and righteousness.

- Spenta Armaiti (Holy Devotion): Symbolizes devotion, piety, and the earth.

- Khshathra Vairya (Desirable Dominion): Associated with strength, power, and the sky.

- Haurvatat (Wholeness): Represents health and completeness.

- Ameretat (Immortality): Embodies eternal life and immortality.

Mithra

Mithra, a significant deity in Persian mythology, is the god of covenant, light, and oath. He is a protector of truth and justice, often depicted as a warrior god who fights against the forces of evil. Mithra’s role as a judge in the afterlife highlights his importance in upholding moral integrity.

Anahita

Anahita, the goddess of waters, fertility, and purity, is another prominent figure. She is associated with life-giving waters, abundance, and the nurturing aspects of nature. Anahita is often depicted as a beautiful and powerful deity, revered for her protective and nurturing qualities.

Verethragna

Verethragna, the god of victory and war, embodies martial prowess and triumph. He is often depicted as a warrior defeating demons and protecting the faithful. Verethragna’s association with strength and courage makes him a revered figure in Persian mythology.

These gods, along with many others, form a complex and dynamic pantheon that reflects the values, beliefs, and aspirations of ancient Persia. Their stories and attributes offer insights into the moral and spiritual principles that underpin Persian mythology.

Creatures

Persian mythology is populated by a diverse array of mythical creatures, each playing a role in the cosmic drama between good and evil. These creatures range from benevolent guardians to malevolent monsters, reflecting the dualistic nature of Persian cosmology.

Simurgh

The Simurgh is a majestic, benevolent creature often depicted as a gigantic bird with peacock-like feathers. It is a symbol of purity, wisdom, and healing. The Simurgh is said to possess immense knowledge and has the power to purify waters and cure diseases. In many myths, it acts as a protector and guide, assisting heroes in their quests.

Griffin (Shirdal)

The Griffin, known as Shirdal in Persian mythology, is a creature with the body of a lion and the head and wings of an eagle. It symbolizes power and protection, often guarding treasures and sacred places. The Griffin represents the merging of terrestrial and celestial attributes, embodying strength and vigilance.

Divs

Divs are malevolent demons and spirits that embody chaos and evil. They serve Ahriman and seek to corrupt and destroy the creation of Ahura Mazda. Divs cause various forms of suffering, from physical ailments to moral decay. They are cunning and relentless, always trying to undermine the forces of good.

Manticore

The Manticore, a fearsome creature with the body of a lion, a human face, and a tail of venomous spines, is another notable figure. It is a symbol of death and destruction, known for its deadly attacks and insatiable appetite for human flesh. The Manticore embodies the dangers and unpredictability of the natural world.

Huma Bird

The Huma Bird is a mythical creature that brings good fortune. It is believed to never alight on the ground and is always in flight, symbolizing eternal freedom and joy. The Huma Bird is said to bestow kingship and luck upon those it flies over, making it a potent symbol of prosperity and success.

These creatures, with their diverse characteristics and roles, add depth and richness to Persian mythology. They embody the complex interplay between good and evil, order and chaos, and reflect the values and fears of the ancient Persian people.

Famous Myths

Persian mythology is replete with captivating myths that have endured through the ages, offering timeless lessons and profound insights. Here are some of the most famous myths from Persian mythology.

The Legend of Rostam and Sohrab

One of the most tragic and well-known tales is that of Rostam and Sohrab, recounted in Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh. Rostam, the greatest hero of Persia, unknowingly battles his own son, Sohrab, whom he had fathered with a princess named Tahmineh. Neither father nor son is aware of their relationship until it is too late. During a fierce duel, Rostam mortally wounds Sohrab. As Sohrab lies dying, he reveals his identity, leaving Rostam grief-stricken and filled with regret. This myth explores themes of fate, heroism, and the tragic consequences of pride and ignorance.

The Story of Jamshid

Jamshid, a legendary king, is a central figure in Persian mythology. His reign is depicted as a golden age, marked by prosperity and advancements in technology and culture. However, Jamshid’s hubris leads to his downfall. Believing himself to be divine, he loses the favor of Ahura Mazda and the loyalty of his people. The demon Zahhak usurps the throne, plunging the world into chaos and darkness. Jamshid’s story serves as a cautionary tale about the dangers of arrogance and the importance of humility and righteousness.

The Creation of the World

According to Persian creation myths, Ahura Mazda created the world in seven stages, each bringing forth a new element of the cosmos. The process began with the creation of the sky, followed by water, earth, plants, animals, and finally humans. This myth underscores the Zoroastrian belief in a divinely ordered universe and the significance of each component of creation.

The Battle of the Twelve Heroes

In this epic tale, twelve Persian heroes, led by Rostam, undertake a perilous journey to rescue the captured king, Kay Kavus, from the clutches of the demon-king, Div-e Sepid. Each hero faces formidable challenges, battling demons and overcoming treacherous obstacles. The tale highlights themes of bravery, loyalty, and the eternal struggle between good and evil.

The End of the World

Eschatological myths in Persian mythology describe the end of the world and the final renovation (Frashokereti). At the end of time, a savior known as Saoshyant will appear, leading the forces of good in a decisive battle against Ahriman and his minions. The world will be purified, the dead will be resurrected, and creation will be restored to its original perfection. This vision of the end times emphasizes the ultimate victory of good over evil and the promise of eternal harmony.

These myths, with their rich narratives and profound themes, continue to resonate with audiences, offering timeless wisdom and a glimpse into the cultural and spiritual heritage of ancient Persia.

Iranian Mythology in the Islamic Period

The advent of Islam in the 7th century brought significant changes to Persian culture and mythology. While many pre-Islamic myths were absorbed and adapted into Islamic literature, they continued to influence Persian storytelling and cultural identity.

Adaptation and Preservation

Under Islamic rule, Persian scholars and poets sought to preserve their cultural heritage by incorporating mythological elements into their works. The Shahnameh, written by Ferdowsi in the 10th century, is a prime example. This epic poem, often referred to as the “Book of Kings,” chronicles the mythological and historical past of Persia, blending Zoroastrian and Islamic themes. Ferdowsi’s work played a crucial role in preserving Persian myths, ensuring their survival and continued relevance.

Syncretism

Islamic Persia witnessed a syncretic blending of pre-Islamic and Islamic elements. Many Zoroastrian concepts and figures were reinterpreted within an Islamic framework. For instance, the Zoroastrian deity Mithra was assimilated into Islamic lore as a figure of light and justice. Similarly, pre-Islamic festivals like Nowruz, the Persian New Year, were adapted to fit within the Islamic calendar while retaining their cultural significance.

Literary Flourishing

The Islamic period saw a flourishing of Persian literature, with poets and writers drawing inspiration from ancient myths. Works like the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam and the poetry of Rumi and Hafez often allude to mythological themes, blending them with Islamic spirituality and philosophy. This literary tradition helped keep the mythological heritage alive, enriching Persian culture and identity.

Cultural Continuity

Despite the profound influence of Islam, many aspects of Persian mythology endured, reflecting a deep-seated cultural continuity. Traditional stories, festivals, and rituals continued to be practiced, often with new Islamic interpretations. This blending of traditions created a unique cultural synthesis, where ancient myths coexisted with Islamic beliefs, enriching the spiritual and cultural tapestry of Persia.

Persian mythology, with its rich narratives and profound themes, offers a window into the soul of an ancient civilization. From the cosmic struggle between Ahura Mazda and Ahriman to the heroic exploits of Rostam and the eschatological vision of Frashokereti, these myths reflect the values, beliefs, and aspirations of the Persian people. They embody a timeless wisdom, offering insights into the nature of good and evil, the purpose of life, and the promise of a just and harmonious world. As we delve into these ancient tales, we not only uncover the cultural and spiritual heritage of Persia but also connect with the universal themes that continue to resonate across time and space.