By Dr. Farshid Emami, Professor of Iranian Literary Studies at Mashhad University

In the vast constellation of Persian poetry, few stars shine with the brilliance and complexity of Awhad ad-Din ‘Ali ibn Mohammad Khavarani, known simply as Anvari. Standing at the pinnacle of the panegyric tradition, yet transcending mere praise through philosophical depth and technical mastery, Anvari represents both the zenith of classical Persian poetic achievement and a fascinating enigma whose life remains shrouded in the mists of time. As we approach the 900th anniversary of his birth, it seems fitting to reexamine this towering figure whose verses continue to resonate through the corridors of Iranian cultural consciousness.

The Shadowed Life of a Luminous Poet

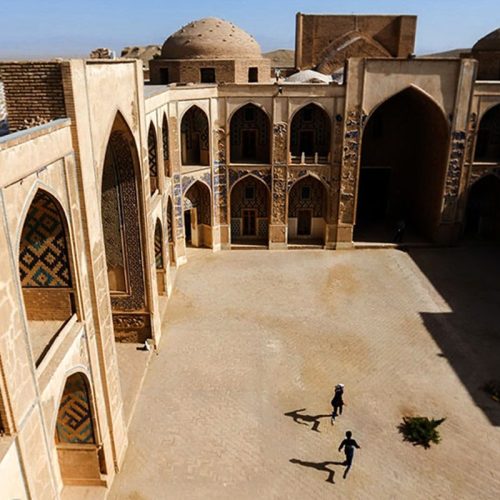

The biographical details of Anvari’s life are as elusive as the meaning of his most complex verses. Born in the late 11th or early 12th century (most likely between 1105-1126 CE) in the town of Abivard in Khorasan (in present-day Turkmenistan), Anvari emerged from the scholarly environment of Tus where he received his education at the prestigious Mansuriyya Madrasa. The name “Anvari” itself—meaning “the illuminated one”—seems prophetic in hindsight, though whether it was bestowed upon him or chosen as a poetic persona remains uncertain.

What distinguishes Anvari’s early years from many of his contemporaries is his formidable education. Before turning to poetry, he immersed himself in the sciences of his age—astronomy, mathematics, logic, and philosophy. The intellectual foundation acquired during these formative years would later inform the startling complexity and originality of his verse. In an age when poets often emerged from modest backgrounds or dedicated themselves to poetry from youth, Anvari represents the scholar-poet whose technical brilliance stems partly from his mastery of multiple domains of knowledge.

The pivotal moment in Anvari’s career came when, according to the oft-repeated anecdote recorded in Nizami Aruzi’s Chahar Maqala (Four Discourses), he witnessed the lavish rewards bestowed upon a court poet by Sultan Sanjar of the Seljuq dynasty. Supposedly, Anvari exclaimed, “Is poetry such a valued accomplishment that it merits such generous remuneration?” and promptly abandoned his scholarly pursuits to dedicate himself to verse. While this account may be apocryphal—designed to emphasize the tension between scholarly and poetic pursuits that Anvari himself would explore in his work—it nevertheless captures something essential about his transition from scholar to poet.

For much of his productive life, Anvari served as a court poet to Sultan Sanjar, producing panegyrics of unparalleled technical brilliance and linguistic innovation. Yet the relationship between poet and patron was not without its complications. When Sanjar was captured by the Ghuzz Turks in 1153, Anvari’s comfortable position at court was undermined. The latter part of his life seems marked by withdrawal from court life, possibly in the face of changing political circumstances and personal disillusionment.

The circumstances of Anvari’s death, like much else in his biography, remain contested. Traditional accounts place his death around 1189-1191 CE, possibly in Balkh or Nishapur. Some narratives suggest he died in poverty and obscurity, having fallen from favor—a fate not uncommon among court poets whose fortunes were inextricably linked to their patrons. Others present a more dignified end, with Anvari retiring to a life of ascetic contemplation, having transcended the very worldly ambitions that drove his poetic career.

This biographic uncertainty itself seems appropriate for a poet whose work constantly grapples with the tension between worldly ambition and spiritual transcendence, between the transitory nature of political power and the enduring quality of artistic achievement.

The Textual Legacy: Mapping Anvari’s Poetic Cosmos

Anvari’s surviving corpus consists primarily of qasidas (formal odes), ghazals (lyric poems), qit’as (fragments or occasional pieces), and ruba’iyat (quatrains). The total number exceeds 2,700 couplets, though attributions remain contested in some cases, as is common with medieval Persian poets. His most celebrated works include his panegyrics to Sultan Sanjar, his philosophical reflections on fate and human insignificance, and his satirical pieces targeting rival poets and social hypocrisy.

Among his most famous individual poems is the “Tears of Khorasan” (Ashk-e Khorasan), a moving lament for his homeland devastated by the Ghuzz invasion. This remarkable political qasida transcends court poetry’s conventional boundaries, offering a poignant meditation on suffering and devastation that resonates across centuries. Similarly, his “Great Qasida” (Qasida-ye Kubra) showcases his technical virtuosity while exploring profound philosophical themes about human existence.

Beyond individual poems, what distinguishes Anvari’s corpus is its remarkable range. He moves effortlessly from expressions of cosmic despair to biting satire, from intricate wordplay to affecting simplicity. In an aesthetic tradition that valued technical accomplishment and innovation within established forms, Anvari pushed the boundaries of what poetry could achieve without abandoning classical structures.

The textual transmission of Anvari’s work presents its own challenges. The earliest surviving manuscripts date from several centuries after his death, raising questions about interpolations and misattributions. The definitive modern edition of his complete works (Divan-e Anvari) was compiled by Mohammad Taqi Modarres Razavi in the mid-20th century, bringing together the most reliable manuscript traditions. Yet uncertainties remain—a fact that both frustrates scholarly precision and creates space for continual reinterpretation of his legacy.

The Jeweled Mirror: Anvari’s Poetic Style

Anvari’s technical brilliance is universally acknowledged, even by critics who question some aspects of his poetic vision. His command of rhetorical devices (especially iham or amphibology—the deliberate use of ambiguous expressions), his unprecedented expansion of Persian poetic vocabulary, and his intricate manipulation of meter and rhyme place him among Persian poetry’s supreme technicians.

What sets Anvari apart from mere technical virtuosos is how he harnesses these skills in service of complex intellectual and emotional content. His astronomical knowledge informs his cosmic imagery; his philosophical training underpins his meditations on fate and human insignificance; his mathematical precision shapes his metrical innovations. The result is poetry of unparalleled density and sophistication—verses that demand and reward close reading across centuries.

Consider these lines from one of his celebrated qasidas, where he reflects on human impermanence against the backdrop of cosmic permanence:

The celestial spheres continue their ancient revolutions,

While we pass like shadows across the earth’s face.

Why place your heart in this transient caravanserai

When tomorrow’s dawn will find no trace of tonight’s guests?

Here, astronomical imagery merges with philosophical reflection and emotional resonance—a characteristic Anvarian synthesis. Similarly, his ability to condense complex ideas into epigrammatic expressions has made many of his lines proverbial in Persian culture:

The world is but a borrowed garden; we merely passing through.

Why build palaces in a space not granted us by deed?

Beyond technical accomplishment and intellectual depth, what distinguishes Anvari’s style is its remarkable combination of precision and passion. Unlike poets who sacrifice emotional impact for technical display, Anvari achieves both simultaneously. His most intricate verses still manage to move the reader, while his most affecting lines reveal new complexities upon closer examination.

Anvari’s use of imagery deserves special attention. Drawing on both natural observation and scientific knowledge, he creates metaphors of startling originality. The sun becomes “the golden peacock of the celestial garden”; the night sky transforms into “the ink-stained page where fate writes its decrees.” These are not merely decorative flourishes but integral components of his poetic argument, connecting sensory experience to abstract thought.

His satirical verses display a different facet of his stylistic range—a razor-sharp wit deployed against hypocrisy and pretension. Here, his language becomes direct, even colloquial, though no less artful. The contrast between these satirical pieces and his elevated philosophical works reveals a poet capable of modulating his voice to serve diverse purposes.

Perhaps most remarkable is Anvari’s self-reflexivity—his poetry frequently comments on the poetic act itself, questioning its purpose and value even while demonstrating its power. This creates a fascinating tension at the heart of his work, as he simultaneously celebrates and interrogates his chosen art form.

Beyond Court Poetry: Anvari’s Intellectual Horizons

Though primarily remembered as a court poet, Anvari’s work transcends the limitations of panegyric. His intellectual preoccupations—the nature of fate, the insignificance of human achievement against cosmic time, the relationship between worldly and spiritual values—place him in conversation with the philosophical traditions of his age.

Particularly notable is Anvari’s engagement with astronomical knowledge. Living in an era when Persian and Islamic astronomy had reached considerable sophistication, Anvari incorporates both observational astronomy and astrological concepts into his poetic worldview. His infamous prediction of catastrophic planetary conjunctions in 1186 CE (which failed to materialize as he foretold) suggests his continued engagement with astronomical calculation even after his primary turn to poetry.

Anvari’s work also reflects the religious complexities of his era. While operating within an Islamic cultural framework, his poetry engages with multiple intellectual traditions—sometimes expressing orthodox piety, other times questioning traditional religious assumptions through philosophical skepticism. This multivalent approach to religious themes reflects the intellectual diversity of Khorasan during the Seljuq period, when various theological schools, mystical movements, and philosophical approaches coexisted in creative tension.

His treatment of fate (qaza and qadar) reveals this complexity. In some verses, he presents a stoic resignation to divine decree; in others, he questions the justice of a cosmos that seems indifferent to human suffering. Rather than resolving these tensions, his poetry explores them from multiple angles, demonstrating how literary expression can accommodate intellectual contradictions that philosophical systems must attempt to resolve.

Particularly fascinating is Anvari’s ambivalent relationship to sufism, the mystical dimension of Islam that was gaining increasing cultural prominence during his lifetime. While not primarily identified as a mystical poet (unlike his near-contemporary Attar or the later Rumi), Anvari nevertheless engages with sufi concepts and imagery, especially in his reflections on worldly detachment and spiritual insight. Yet he approaches these themes with characteristic intellectual complexity, neither fully embracing mystical perspectives nor dismissing them.

The Mirror and the Lamp: Anvari’s Influence on Persian Literary Tradition

Anvari’s influence on subsequent Persian poetry has been both profound and complex. For generations of poets, he represented the pinnacle of technical accomplishment in the qasida form—a standard against which to measure their own achievements. His innovations in poetic language and imagery expanded the expressive possibilities available to later writers.

The 13th-century poet and critic Shams-e Qays Razi acknowledged Anvari’s supreme position in the technical hierarchy of Persian poetry, while expressing reservations about some aspects of his style. This ambivalence characterizes much of the critical reception of Anvari’s work—admiration for his technical brilliance tempered by concerns about his occasional obscurity or excessive complexity.

Despite these reservations, Anvari’s status as one of Persian poetry’s defining masters remained secure. Later poets like Khaqani, while developing their own distinctive styles, acknowledged their debt to Anvari’s innovations. Even poets working in different forms, like the ghazal-master Hafez, occasionally echo Anvarian expressions and themes.

Beyond specific influences on individual poets, Anvari helped establish certain enduring patterns in Persian poetic culture: the valorization of difficulty and complexity as aesthetic virtues; the integration of philosophical reflection into formal poetry; and the self-conscious exploration of poetry’s own purposes and limitations.

His influence extended beyond Persian literary culture proper. As Persian became a literary language throughout much of the Islamic world, Anvari’s work became a model for poets writing in Turkish, Urdu, and other languages influenced by Persian literary standards. The technical standards he established shaped poetic practice across cultural and linguistic boundaries.

Contemporary Resonances: Anvari in Modern Iranian Culture

In contemporary Iran, Anvari occupies a somewhat paradoxical position. While acknowledged as one of the supreme masters of classical tradition, his work has not achieved the popular resonance of poets like Hafez, Sa’di, or Rumi. Several factors may explain this relative marginalization in popular culture.

First, Anvari’s technical complexity makes his work less accessible to casual readers. Unlike Hafez’s ghazals or Rumi’s mystical narratives, which can be appreciated on multiple levels, Anvari’s dense qasidas require considerable literary knowledge and close reading. Second, the panegyric form itself—despite Anvari’s transcendence of its limitations—has less immediate appeal to modern sensibilities than lyric or narrative poetry.

Nevertheless, Anvari’s significance in scholarly and literary circles remains undiminished. Modern Iranian critics like Mohammad Reza Shafi’i Kadkani have offered fresh interpretations of his work, emphasizing how his technical innovations serve profound intellectual and emotional purposes. Contemporary poets engaged with classical forms continue to study Anvari as a master of poetic craft whose achievements remain unsurpassed.

What speaks most powerfully to contemporary Iranian cultural concerns is Anvari’s exploration of the tensions between power and poetry, between worldly ambition and spiritual insight. In a society continually negotiating the relationship between Persian cultural heritage and modern challenges, Anvari’s self-reflexive questioning of poetry’s purpose has renewed relevance.

Particularly resonant is Anvari’s ambivalent relationship to power. As a court poet, he participated in the political culture of his time, celebrating Seljuq achievements and legitimizing Sanjar’s rule. Yet his most enduring works often question the very structures of power they ostensibly celebrate, suggesting a complex consciousness that both participated in and stood apart from the political order of his day.

This tension between engagement and detachment, between celebration and critique, seems especially relevant in contemporary Iran, where poets and intellectuals continue to navigate complex relationships with political power. Anvari offers no simple model for resolving these tensions, but his work demonstrates how literary expression can acknowledge such contradictions without reducing them to facile resolutions.

Beyond the Horizon: New Directions in Anvari Studies

Recent scholarship has opened new avenues for understanding Anvari’s work and significance. Interdisciplinary approaches connecting his poetry to the scientific and philosophical developments of the Seljuq period have revealed how deeply his poetic innovations were rooted in the intellectual culture of his time.

Comparative studies placing Anvari alongside other major world poets concerned with similar themes—power, impermanence, the limitations of human knowledge—offer fresh perspectives on his achievement. While firmly rooted in Persian cultural traditions, Anvari’s explorations of universal human concerns invite such comparative approaches.

Manuscript studies continue to refine our understanding of his textual legacy, occasionally yielding new attributions or questioning traditional ones. Digital humanities approaches, bringing computational analysis to bear on questions of style and attribution, promise to further illuminate the contours of his corpus.

Perhaps most promising are interpretive approaches that recognize the multidimensional quality of Anvari’s poetry—its simultaneous operation on technical, intellectual, political, and spiritual levels. Rather than privileging any single dimension of his work, such approaches explore how these various aspects interact within individual poems and across his oeuvre.

The Unending Orbit: Concluding Reflections

Anvari’s poetry continues to circulate in Iranian cultural consciousness like the celestial bodies he so often invoked in his verses—a constant presence whose significance shifts with changing perspectives. Nine centuries after his birth, his technical brilliance remains unsurpassed, his philosophical inquiries still provocative, his exploration of poetry’s purposes still relevant.

What makes Anvari crucial to understanding Persian literary tradition is precisely his embodiment of its central paradoxes: the tension between technical mastery and emotional directness; between worldly engagement and spiritual detachment; between tradition and innovation; between clarity and productive ambiguity. Rather than resolving these tensions, his poetry explores them from multiple perspectives, creating a body of work remarkable for both its coherence and its internal diversity.

For contemporary readers, Anvari offers no single message or moral. Instead, his poetry demonstrates how literary expression can accommodate complexity and contradiction—intellectual, emotional, spiritual, political—without reducing it to simplistic formulations. In an age often characterized by reductive polarizations, this capacity to hold multiple perspectives in productive tension may be his most valuable legacy.

As we approach the millennium of his birth, Anvari remains what he has always been: a poet who pushes language to its limits in exploration of human experience in all its dimensions. The astronomical imagery that pervades his work seems appropriate to his enduring significance—a fixed star in Persian literature’s firmament whose light continues to illuminate new pathways of understanding and appreciation.

Like the celestial bodies whose movements he studied and transformed into metaphor, Anvari completes his poetic orbit across centuries, returning always as both familiar presence and new discovery. His verses, as he himself might have predicted, have outlasted the political powers they sometimes celebrated, enduring as testimony to poetry’s capacity to transcend its immediate circumstances and speak across time.

In the unending conversation that constitutes Persian literary tradition, Anvari’s voice remains distinct and essential—technical yet passionate, learned yet direct, celebrating beauty while acknowledging impermanence. Nine centuries after he first crafted his verses in the courts of Khorasan, we remain within the orbit of his poetic achievement, continually discovering new dimensions in work that exemplifies Persian poetry at its most accomplished and profound.