By Dr. Mahmoud Rahmani Department of Persian Literature and Poetry Studies University of Tehran

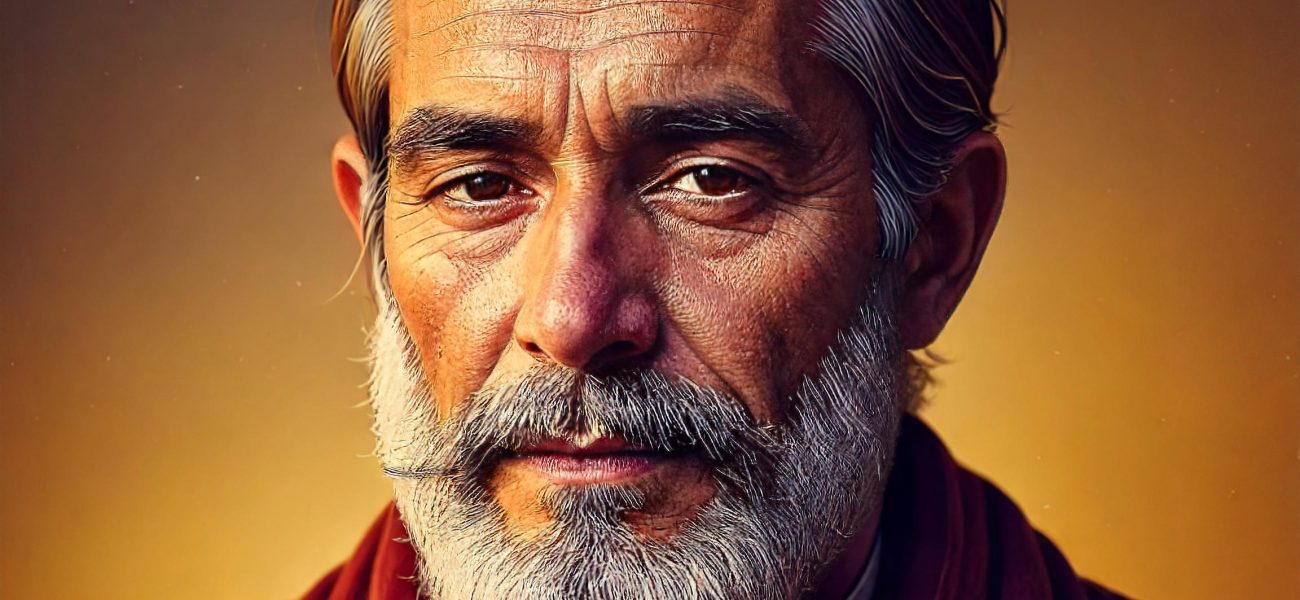

In the shimmering tapestry of medieval Persian poetry, few threads gleam with the peculiar brilliance of Suzani Samarqandi, whose verses cut through the perfumed air of 12th-century Transoxiana like a well-honed blade. Born Muhammad ibn Ali Samarqandi around 1091 CE in or near the resplendent city of Samarqand, he would come to be known by the pen name “Suzani” – literally “needle-wielder” – an apt moniker for a poet whose words could stitch together the most delicate praise or pierce the thickest armor of pretension.

As I sit here in my study in Tehran, surrounded by manuscripts and collections of medieval Persian poetry, I find myself returning again and again to Suzani’s works, marveling at how a voice from nearly a millennium ago can speak with such startling contemporaneity. His satires, though rooted in the particular social and political landscape of 12th-century Central Asia, contain insights into human nature that transcend both time and culture.

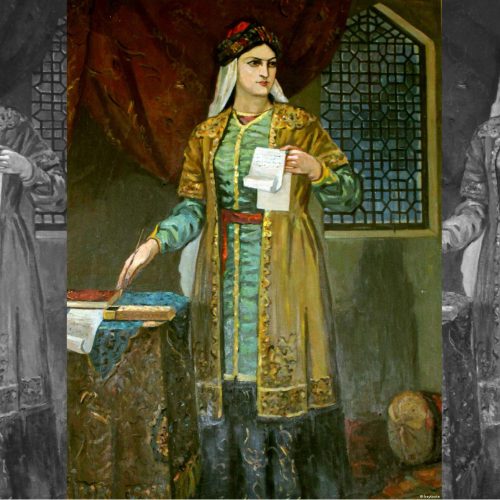

The Samarqand of Suzani’s time was a jewel in the crown of Islamic civilization, a center of learning and culture where the streets buzzed with the languages of the Silk Road – Persian, Turkish, Arabic, and countless others. The city’s bazaars overflowed with goods from China to Byzantium, its madrasas echoed with scholarly debates, and its courts resonated with the refined verses of poets seeking patronage. It was in this cosmopolitan crucible that Suzani’s distinctive poetic voice was forged.

What sets Suzani apart from his contemporaries is not merely his mastery of form – though his command of the technical aspects of Persian poetry was indeed formidable – but rather his willingness to deploy that mastery in service of satire that spared neither high nor low. While other poets of his era confined themselves largely to panegyrics and romantic ghazals, Suzani turned his pen to subjects that many considered beneath poetic dignity.

Consider these lines, which I translate with some hesitation, given their characteristic earthiness:

“That preacher who speaks of paradise and hell, His sermon’s as empty as his morning meal’s smell. He warns of the fire while his pocket grows fat, The only true burning’s the shame of his chat.”

The translation, admittedly, captures but a shadow of the original Persian, where the interplay of sounds and meanings creates layers of wit that resist rendering in any other tongue. Yet even in translation, we can discern Suzani’s signature combination of technical sophistication and unsparing social criticism.

Suzani’s work presents us with a fascinating paradox. While he was renowned (and sometimes feared) for his satirical verses, he was also a master of the panegyric form, composing praise poems for various rulers and nobles of his time. These were not mere exercises in flattery, but rather complex works that often contained subtle criticism wrapped in the gleaming garments of praise. His patron-seeking verses to the Qarakhanid rulers of Samarqand reveal a poet who understood the delicate dance of court politics while maintaining his artistic integrity.

The poet’s personal life remains somewhat obscure, though we know he married at least twice and had several children. His poetry suggests a man who lived life fully and unapologetically, who understood both the pleasures and pains of human existence. He was known to frequent the taverns of Samarqand, not merely as a consumer of wine but as an observer of human nature in all its unvarnished reality.

What strikes me most powerfully about Suzani’s work is its startling modernity. While many medieval Persian poets seem to speak to us from behind a veil of conventional imagery and established tropes, Suzani’s voice cuts through the centuries with remarkable clarity. His concerns – social hypocrisy, religious pretension, political corruption, and human folly – remain remarkably relevant to our own time.

Consider his famous satire of a wealthy merchant:

“His coins pile high like mountains of gold, While his heart shrivels, withered and old. He counts and recounts his glittering heap, Not knowing the price of a night’s peaceful sleep.”

These lines could easily apply to many of today’s wealthy elite, suggesting that human nature has changed little in the intervening centuries.

Suzani’s influence on Persian literature, while significant, has perhaps been underappreciated due to the very qualities that make him unique. His willingness to engage with the earthier aspects of human existence, his biting satire, and his occasional crudeness have led some scholars to marginalize him in favor of more “respectable” poets. This, I believe, is a mistake.

The technical sophistication of Suzani’s verse is often overlooked in discussions of his more controversial content. His mastery of various poetic forms – from the qasida to the ghazal to the qit’a – demonstrates a deep understanding of the Persian poetic tradition. His wordplay and use of double entendre reveal a mind of exceptional agility, while his manipulation of meter and rhyme shows complete command of the technical aspects of poetry.

What makes Suzani particularly fascinating to modern readers is his role as a social chronicler of his time. Through his verses, we glimpse the everyday life of 12th-century Samarqand in a way that more conventional historical sources cannot provide. His satires of merchants, religious figures, and government officials offer invaluable insights into the social dynamics of medieval Central Asia.

The poet’s relationship with religion deserves special attention. While he frequently satirized religious hypocrisy, his works demonstrate a deep familiarity with Islamic teachings and traditions. His criticism was directed not at faith itself, but at those who used religion as a mask for worldly ambition or personal gain. This nuanced approach to religious criticism remains relevant in our own time, when discussions of faith and society often lack such sophistication.

Suzani’s work also provides valuable insights into the multilingual nature of medieval Central Asian society. His poetry contains words and phrases from Turkish and Arabic, reflecting the linguistic diversity of Samarqand. This multilingual dimension adds another layer of complexity to his wordplay and demonstrates the cosmopolitan nature of medieval Central Asian culture.

The poet’s influence can be traced through subsequent generations of Persian poets, particularly those who worked in satirical modes. While few dared to be as bold in their criticism as Suzani, his technical innovations and willingness to engage with social issues inspired many followers. His influence can be detected in the works of poets as diverse as Ubayd Zakani in the 14th century and Iraj Mirza in the early 20th century.

From my perspective as a contemporary Iranian scholar, Suzani’s relevance to modern Persian literature and culture cannot be overstated. His fearless approach to social criticism, his technical mastery, and his ability to combine high artistic achievement with popular appeal offer important lessons for contemporary writers and poets.

The manuscript tradition of Suzani’s work presents numerous challenges to modern scholars. Many of his poems survive only in fragments or in later collections, and attribution can sometimes be problematic. Additionally, the frank nature of some of his verses led to their being expurgated or modified by later copyists. Despite these challenges, enough of his work survives to establish his significance in the Persian poetic tradition.

Suzani died around 1166 CE, leaving behind a body of work that continues to challenge and inspire readers. His tomb in Samarqand became a minor pilgrimage site for lovers of poetry, though its exact location has been lost to time. Perhaps this is fitting for a poet who seemed to care little for worldly monuments, preferring to let his verses speak for themselves.

As we approach the thousand-year anniversary of Suzani’s birth, it seems appropriate to reassess his place in the Persian literary canon. While he may never achieve the widespread recognition accorded to poets like Rumi or Hafez, his unique voice and perspective deserve greater attention from both scholars and general readers.

His verse about the transience of fame seems particularly appropriate:

“Let others build towers that scrape heaven’s dome, I’ll craft words that make human hearts their home. Their stones will crumble, their gold will decay, But truth spoken boldly will find its own way.”

In our current age, when social media and instant communication have made satire both more prevalent and often more superficial, Suzani’s sophisticated approach to social criticism offers valuable lessons. His ability to combine technical excellence with social commentary, humor with serious purpose, and personal observation with universal truth provides a model for contemporary writers and artists.

As I conclude this reflection on Suzani’s life and work, I am struck by how much we still have to learn from this sharp-tongued poet of medieval Samarqand. His verses remind us that great literature need not choose between artistic excellence and social relevance, between technical sophistication and popular appeal, between tradition and innovation.

In the end, perhaps Suzani’s greatest achievement was to demonstrate that poetry could be both high art and a vehicle for social criticism, that it could make us laugh while making us think, and that it could speak truth to power while celebrating the full range of human experience. These are lessons that remain valuable today, as we continue to grapple with many of the same human foibles and social issues that Suzani addressed with such wit and wisdom nearly a millennium ago.

The needle-wielder of Samarqand may have laid down his pen centuries ago, but his verses continue to stitch together the past and present, reminding us that great literature, like truth itself, knows no boundaries of time or place. In studying Suzani, we not only learn about a fascinating period in Persian literary history but also gain insights into our own time and our own human nature.