By Dr. Fatemeh Rahimi Department of Persian Literature University of Tabriz

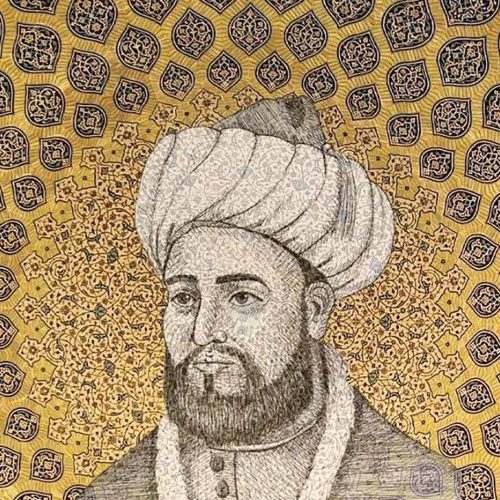

The literary landscape of medieval Persia bears the indelible imprint of Abu Mansur Ali ibn Ahmad Asadi Tusi, a towering figure whose contributions to Persian literature and linguistics continue to resonate through the corridors of time. As we delve into the life and works of this 11th-century master, we uncover not merely a poet or lexicographer, but a visionary who helped shape the very foundation of Persian literary tradition during a pivotal period of Iranian cultural renaissance.

Life: A Journey Through Tumultuous Times

The precise date of Asadi Tusi’s birth remains shrouded in the mists of history, though scholarly consensus places it in the late 10th or early 11th century in the city of Tus, in the Greater Khorasan region. This was an era of profound political and cultural transformation in the Iranian world, as the Ghaznavid dynasty’s influence waned and the Seljuq Turks emerged as the new power brokers of Western Asia.

Born into this dynamic milieu, Asadi Tusi’s early life was steeped in the rich cultural heritage of Khorasan, a region long renowned as a crucible of Persian literary and intellectual achievement. The young Asadi benefited from the region’s sophisticated educational tradition, mastering Arabic, becoming well-versed in pre-Islamic Iranian legends, and developing the linguistic precision that would later distinguish his works.

The political instability that marked the transition from Ghaznavid to Seljuq rule proved to be a defining factor in Asadi’s life. Like many scholars of his time, he was forced to seek patronage away from his homeland. This led him to Azerbaijan, where he found refuge in the court of Abu Dulaf, the local ruler of Nakhchivan. This geographical displacement, while personally challenging, would prove fortuitous for Persian literature, as it was under Abu Dulaf’s patronage that Asadi would produce his most significant works.

The Azerbaijan period represents the most productive phase of Asadi’s career. Here, surrounded by a different linguistic and cultural environment, his appreciation for his native Persian deepened, spurring him to undertake works that would preserve and elevate the language. His experience as a cultural émigré imbued his writings with a particular sensitivity to questions of Iranian identity and linguistic heritage.

What distinguishes Asadi’s life narrative from many of his contemporaries is his dual role as both inheritor and innovator of Persian literary traditions. While he drew deeply from the well of ancient Iranian mythology and pre-Islamic history, he was not content merely to preserve these traditions. Instead, he actively reshaped them for his contemporary audience, adding layers of philosophical and theological sophistication that reflected the intellectual concerns of his time.

Works: A Legacy of Literary Innovation

Garshaspnama: Reimagining the Epic Tradition

The Garshaspnama, completed in 1066 CE, stands as Asadi Tusi’s magnum opus and represents a significant evolution in the tradition of Persian epic poetry. This work, comprising approximately 9,000 couplets, recounts the adventures of the legendary hero Garshasp, a figure whose origins trace back to ancient Iranian mythology. However, Asadi’s treatment of this material transcends mere storytelling; it represents a sophisticated attempt to merge heroic narrative with philosophical discourse.

The epic’s significance lies not only in its artistic merit but in its relationship to Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh. While clearly influenced by his predecessor’s work, Asadi crafted something distinctly different. Where Ferdowsi focused primarily on the narrative sweep of Iranian history and legend, Asadi infused his epic with detailed philosophical discussions and scientific digressions. His hero, Garshasp, is not merely a warrior but a sage who engages in profound debates about the nature of existence, faith, and knowledge.

The Garshaspnama is particularly notable for its detailed descriptions of India, reflecting both the historical connections between Iran and the subcontinent and Asadi’s own scholarly interest in geography and cultural exchange. His vivid portrayals of Indian customs, flora, and fauna suggest either personal experience or access to detailed sources now lost to us.

Loḡat-e fors: Preserving Linguistic Heritage

Perhaps Asadi’s most enduring contribution to Persian culture is his Loḡat-e fors, the first comprehensive dictionary of Persian poetic vocabulary. This groundbreaking work, composed in his later years, reflects both his deep concern for the preservation of pure Persian vocabulary and his practical experience as a poet and scholar working in a multilingual environment.

The Loḡat-e fors is far more than a simple lexicon. It represents a conscious effort to preserve and promote Persian vocabulary at a time when Arabic words were increasingly dominant in literary and scholarly discourse. Asadi’s methodology was revolutionary for his time. He organized words thematically rather than alphabetically, provided extensive examples from contemporary and classical poetry, and included detailed explanations of usage and meaning.

What makes this work particularly valuable for modern scholars is Asadi’s inclusion of numerous quotations from poets whose works have otherwise been lost to time. These preserved fragments offer invaluable insights into the development of Persian poetry in the early Islamic period. Moreover, his focus on specifically Khorasani dialect words has proved invaluable for understanding the regional variations in medieval Persian.

Monāẓarāt: The Art of Philosophical Debate

Asadi’s Monāẓarāt (debates) represent a unique contribution to Persian literature, combining the traditional Arabic debate format with distinctly Persian literary sensibilities. These works, consisting of four known debates between paired concepts (such as Night and Day, Heaven and Earth), showcase Asadi’s mastery of both form and philosophical discourse.

The debates are remarkable for their sophisticated argumentation and their blend of scientific knowledge with poetic expression. Each participant in these debates presents not only logical arguments but also draws upon astronomy, medicine, theology, and natural philosophy to support their position. This integration of scientific knowledge with literary art reflects the holistic intellectual culture of medieval Iran.

The philosophical depth of these debates reveals Asadi’s engagement with the major intellectual currents of his time. His treatment of theological and philosophical questions shows familiarity with both Islamic scholastic theology (kalām) and neo-Platonic philosophy. Yet he presents these complex ideas in accessible poetic form, demonstrating his skill in making sophisticated concepts comprehensible to a broader audience.

Literary and Historical Significance

Asadi Tusi’s significance extends far beyond his individual works. He represents a crucial link in the chain of Persian literary development, building upon the foundation laid by Ferdowsi while opening new paths for future generations. His influence can be traced in several key areas:

First, his Garshaspnama established a model for incorporating philosophical and scientific discourse into epic poetry, influencing later poets who sought to combine narrative with intellectual content. This synthesis of storytelling and scholarship became a hallmark of medieval Persian literature.

Second, his lexicographical work in Loḡat-e fors played a crucial role in standardizing Persian poetic vocabulary and preserving linguistic heritage. This work not only aided contemporary poets but has proved invaluable for modern scholars studying the development of the Persian language.

Third, his Monāẓarāt helped establish debate poetry as a distinct genre in Persian literature, demonstrating how Persian could be used for sophisticated philosophical discourse. This contribution was particularly significant at a time when Arabic was still the dominant language of philosophical and theological discussion.

Conclusion: A Legacy Renewed

As we reflect on Asadi Tusi’s contributions from our contemporary vantage point, what emerges is the portrait of a scholar who understood that cultural preservation requires not just conservation but active engagement and innovation. His work demonstrates that tradition and innovation are not opposing forces but complementary aspects of cultural development.

The continued relevance of Asadi’s works in contemporary Iranian studies speaks to their enduring value. His concern for linguistic preservation resonates in current debates about language policy and cultural identity. His sophisticated integration of scientific and philosophical knowledge with literary expression offers a model for modern intellectual discourse.

As Iran continues to negotiate its relationship with both tradition and modernity, Asadi Tusi’s legacy offers valuable insights. His works remind us that cultural authenticity does not require rigid adherence to past forms but can embrace innovation while maintaining connection with historical roots. In this sense, Asadi speaks not only to his own time but to ours as well.

His life and works embody the dynamism of Persian culture during a crucial period of transition, demonstrating how individual genius can shape and preserve cultural heritage even in times of political and social upheaval. As we continue to study and analyze his contributions, new layers of meaning and significance emerge, ensuring that Asadi Tusi’s influence remains vital in the ongoing development of Persian literary and intellectual traditions.

Dr. Fatemeh Rahimi is a Professor of Persian Literature at the University of Tabriz, specializing in medieval Persian poetry and lexicography. Her recent publications include “Philosophical Dimensions in Medieval Persian Epic Poetry” and “The Evolution of Persian Literary Language: From Asadi to Nizami.”